Importing Constituents: Prisoners and Political Clout in Texas

By Peter Wagner and Rose Heyer

November 8, 2004

The Census Bureau counts prisoners not at their homes but as if they were residents of the town that contained the prison. This administrative quirk reduces the population of the urban communities where most prisoners originate and swells the population of the rural communities that house prisons. Texas now incarcerates more than 5 times as many people as it did as recently as 1980, making what would once be a trivial issue into a critical one.[1]

When the Census began in 1790, demographics-based planning and redistricting did not yet exist. The Census' sole constitutional mandate was and is to count the number of people in each state to determine their relative populations for purposes of Congressional reapportionment. It didn't matter -- for purposes of comparing Texas' population to California's -- whether an incarcerated person was counted at home in Houston or in prison in Huntsville, as long as they were counted in Texas. Times have changed but Census methodology has not.

County shifts - Texas highlights

In our national research[2], we found 21 counties where at least 21% of the population reported in the Census was incarcerated. Ten of these counties were in Texas. A full third of tiny Concho County (population 3,966) is behind bars, but the numerous large prisons near Huntsville can even put populous counties like Walker County on the list.[3]

Counting incarcerated people as if they were residents of the prison town leads to misleading portrayals of which counties are growing and which are declining. (Declining populations are often a sign of economic distress.) A total of ten counties in Texas were reported in Census 2000 as growing during the previous decade when they actually shrank. By Census figures, Jones County was growing faster than the state average[4], but during the previous decade, 355 residents of Jones County chose to pack up and leave the county. That loss was camouflaged only by the state of Texas sending 4,650 prisoners to be incarcerated there.

Urban and Black communities are the losers in Census count

Prisoners disproportionately come from Texas's largest counties. Harris County is 16.3% of the Texas population, but it supplies 21.5% of the state's prisoners.[5] After adjusting for correctional facilities within the county, Harris County's suffered a net loss of about 25,000 people as a result of how prisoners are counted.

Dallas County is only 10.6% of the Texas population, but it supplies 15.4% of the state's prisoners.[6] This urban county lost almost 20,000 residents to rural prison hosting counties.

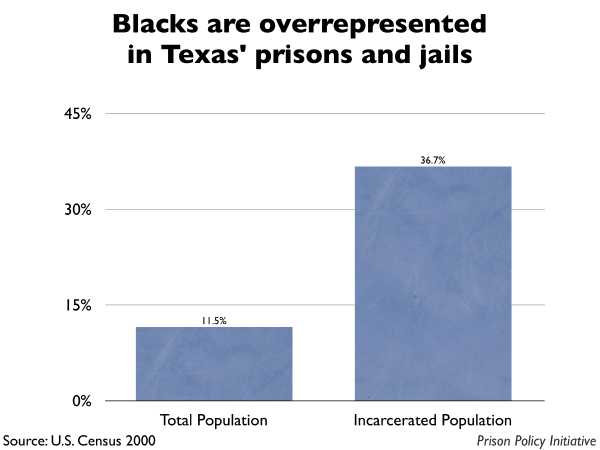

How the incarcerated are counted in Texas is of critical importance to an accurate count of Black communities. While Blacks are 11.5% of the Texas population, more than a third of the incarcerated people in the state are Black. (See Figure 1.) Blacks in Texas are incarcerated at a rate 5 times higher than White residents of the state.[7]

Figure 1. Incarceration in Texas disproportionately affects Blacks. Source: U.S. Census 2000

Texas election law says prison is not a residence

The Texas election law statute, like that of most states, defines residence as the place that you willingly choose to be and explicitly states that a prison can not be a residence.

"§ 1.015. RESIDENCE. (a) In this code, "residence" means domicile, that is, one's home and fixed place of habitation to which one intends to return after any temporary absence.

(b) Residence shall be determined in accordance with the common-law rules, as enunciated by the courts of this state, except as otherwise provided by this code.

(c) A person does not lose the person's residence by leaving the person's home to go to another place for temporary purposes only.

(d) A person does not acquire a residence in a place to which the person has come for temporary purposes only and without the intention of making that place the person's home.

(e) A person who is an inmate in a penal institution or who is an involuntary inmate in a hospital or eleemosynary institution does not, while an inmate, acquire residence at the place where the institution is located."[8] (emphasis added)

The U.S. Census does not bother to determine where a prisoner's residence actually is, but to fairly draw state legislative boundaries, the state legislature is required to determine the true residence of its citizens.

As this report illustrates, the incarcerated population in Texas is now so large that it is no longer possible to ignore the fact that the Texas election law requires data different from that provided by the Census Bureau.

Redistricting and One Person One Vote

Texas, like most states, relies on Census Bureau data to redraw its state legislative boundaries so that each will contain the same number of people as required by the 14th Amendment's One Person One Vote rule. Equally sized districts ensure that each resident has an equal access to government regardless of where she or he lives. The Census counts everyone including people who can't vote such as prisoners and children. But children are at least a part of the surrounding community and share some common interests with it. Children can with some confidence rely on their neighboring adults to represent their interests. But prison communities are often very closely aligned with the prison industry and are likely to be quite dissimilar to the communities that the prisoners came from.

The basic principle of American representative democracy is that every vote must be of equal weight. The starting point for state legislative redistricting is the landmark 1963 Supreme Court case Reynolds v. Sims.[9] Reynolds struck down an apportionment scheme for the Alabama state legislature that was based on counties and not population. In 1960 Alabama, Lowndes County with 15,417 people had the same number of state senators as Jefferson County with 634,864 people. Believing the situation in Alabama to be illustrative of a large number of other states drawing legislative boundaries in such as way as to dilute the political power of citizens based on where they lived, the Supreme Court wrote a very broad opinion to guide the states in fairly apportioning the state legislatures.

If districts are of equal size, each citizen has equal access to a representative to advocate for her or his needs. When districts are of substantially different sizes, the weight of each vote starts to differ. In underpopulated districts, each vote is worth more, and in overpopulated districts, a vote is worth less. In 1960 Alabama, a Lowndes County senator had the same political power as one from Jefferson County, but the Lowndes County senator could devote her or himself to advancing the interests of only 15,417 people. As a result, a vote in Lowndes county was worth over 41 times a vote in Jefferson county. Reynolds v. Sims barred this practice and put it plainly: "[T]he weight of a citizen's vote cannot be made to depend on where he lives."[10]

Every urban prisoner counted as a rural resident decreases the number of "real" rural residents required for a rural district. As the number of real residents declines, the weight of a vote from a rural resident increases. This undemocratic effect is magnified by the fact that most "phantom" rural residents in a rural prison should have been counted in an urban area.

Congressional Districts

Based on Article 2 of the U.S. Constitution, congressional districts are required to be based on equal population "as nearly as is practicable."[11] Each of Texas' 32 Congressional districts contain 651,619 or 651,620 people. This is true for the current districts and those that will take effect with the November 2004 elections.

In our analysis of the new Congressional plan, we found 12 districts that contain more than 10,000 incarcerated people. (See Appendix C and Figure 2.) Districts 8 (which includes Walker County) and 13 (on the Texas panhandle) each contain more than 20,000 incarcerated people. More than 3% of the population credited to these districts actually resides somewhere else. Every group of 97 residents in these districts is represented as if they were 100 residents elsewhere in the state. The One Person One Vote rule was designed to prevent legislators from trying to equate 97 votes in one place with 100 votes somewhere else.

Figure 2. Incarcerated populations in Texas Congressional districts

Texas Legislative Districts

The U.S. Constitution allows state legislative districts to make small deviations from strict population equality in order to preserve existing community boundaries and protect "communities of interest." The general rule is that districts must not be more than 5% above or below the ideal district size. The drafters of the Texas House and Senate districts keep the deviations of Census population under this limit, yet this careful effort may have been for naught. In one House district, almost 12% of the Census population consists not of residents but of incarcerated "unwilling sojourners".[12]

The ideal Texas House district is supposed to contain 139,012 residents and a Senate district 672,639 residents. The current House Districts vary from 132,316 to 145,847, a total deviation of 13,531 or 9.74%. The Texas Senate districts vary from 639,525 to 704,875, for a total deviation of 65,350 or 9.71%. The plans of both chambers come relatively close to Census population equality, with the average House district deviating by 2.65% and the average Senate district by 2.60% from the target populations. But unfortunately, the Census populations used to draw Texas' population are not reflective of Texas' population. As the below tables illustrate, the number of prisoners in many Texas legislative districts is significant by constitutional standards.

In 8 House districts more than 5% of the district population is incarcerated. In two districts, (District 13 near Walker County, represented by Republican Lois Kolkhorst and District 8 near Anderson County represented by Republican Bryan Cook) almost 12% of the district's Census population is incarcerated.[13]

| House District | Representative (Oct 2004) | Party (Oct 2004) | Located near | Incarcerated population | Percent of district that is incarcerated | District population |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | Cook, Byron | R | Anderson County | 16,446 | 11.73% | 140,151 |

| 13 | Kolkhorst, Lois | R | Walker County | 16,670 | 11.97% | 139,273 |

| 18 | Ellis, Dan | D | Liberty and Polk Counties | 7,678 | 5.62% | 136,678 |

| 22 | Deshotel, Joseph "Joe" | D | Jefferson County | 7,043 | 5.29% | 133,159 |

| 35 | Canales, Gabi | D | Bee County | 12,239 | 8.39% | 145,847 |

| 59 | Miller, Sid | R | Hamilton County | 9,146 | 6.43% | 142,194 |

| 85 | Laney, James "Pete" | D | Surrounding (but not including) Lubbock County | 11,605 | 7.97% | 145,561 |

| 100 | Hodge, Terri | D | Dallas | 7,710 | 5.38% | 143,335 |

Figure 3. Incarcerated populations in Texas House districts.

In the Texas Senate, 3 districts have more than 20,000 incarcerated people. District 3, near Anderson County, represented by Republican Todd Staples has 23,319 people behind bars. District 5, near Walker County, represented by Republican Steve Ogden, has 28,318 imprisoned "constituents" and District 28 represented by Republican Robert L. Duncan appears to have the correct population only by including 21,801 prisoners.

| Senate District | Senator (Oct 2004) | Party (Oct 2004) | Located near | Incarcerated population | Percent of district that is incarcerated | District population |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | Todd Staples | Republican | Anderson County | 23,319 | 3.33% | 701,284 |

| 5 | Steve Ogden | Republican | Walker County | 28,318 | 4.26% | 665,214 |

| 28 | Robert L. Duncan | Republican | Lubbock County | 21,801 | 3.24% | 673,890 |

Figure 4. Incarcerated populations in Texas Senate districts.

When the Supreme Court allows districts to deviate in population by 5% from the ideal district size, it does so to allow the districts to avoid splitting a particular "community of interest" or crossing an existing community boundaries. (In the context of sparsely populated rural districts, these two concepts are often the same. ) The underlying rationale is that needlessly dividing counties between districts would make it harder for the residents of the split communities to be heard at the state level. The Supreme Court established this general rule of no more than a 5% deviation from population equality as the line between the harm caused by unequal district sizes and splitting communities of interest.

Looking at House Districts 8 and 13, the prisoner-count based distortion of electoral power in Texas is by itself twice the Supreme Court's allowable measure of deviation to preserve legitimate communities of interest. But counting urban prisoners as rural residents violates the very ideas of starting with population and deviating from perfect equality only to preserve traditional "communities of interest". Prisoners are external populations that are not "traditionally" rural in any sense of the word. Allowing communities to take in populations by force, just to benefit at the state legislature, violates any sense of equal protection or fundamental fairness. As Chief Justice Warren instructed in Reynolds v. Sims, laying down the principle of one person one vote: "Legislators represent people, not trees or acres. Legislators are elected by voters, not farms or cities."[14] Nor, we might add, should they be elected by the presence of a prison.

State-level options to reverse Census distortions

Texas need not wait for the Census Bureau to change how it counts prisoners in order to fairly divide its population between legislative districts, as it could adjust the Census Bureau's data prior to redistricting in order to match the data to its own requirements of residence. Kansas currently does this with students and military personnel, and in 2001 Texas Representative Harold Dutton (D, Houston) introduced legislation that would have adjusted the Census Bureau's count of the incarcerated prior to redistricting.[15]

Although Representative Dutton's bill was approved by the Elections committee, it was not ultimately successful. However, the bill does describe a mechanism by which states can collect prisoner residence data to correct Census Bureau counts.

Representative Dutton's bill required state and local governments (and requests the federal government) to provide the Texas Comptroller the name, age, race, ethnicity and last known address of every person counted in a correctional facility on Census day. The counts for incarcerated persons with a last known addresses outside of Texas would remain unadjusted, but the Texas Comptroller would subtract Texas prisoners from the facility's census count and add the prisoner to the counts for his or her home address. Rather than require the use of this dataset in all state and local redistricting, the proposed legislation required that any districts drawn did not deviate from the corrected dataset by more than 5%. In effect, the bill was a minimalist attempt to ensure that prison towns and high incarceration neighborhoods would not receive unwarranted vote concentration or vote dilution.

Given the compressed timetable of the redistricting process, it is not surprising that this bill was not ultimately successful; but it does provide an additional lesson in the importance of addressing the shortcomings of the Census Bureau's methodology sooner rather than later.

Recommendations

Census Bureau policy on how to count the population is not fixed, instead it responds to changing needs. When evolving demographics meant more college students studying far from home and more Americans living overseas, the Census policy changed in order to more accurately reflect how many Americans were living where. Today, the growth in the prisoner population requires the Census to update its methodology once again.

The Census Bureau should update its methodology and count the incarcerated at their homes and not in remote prison cells. Until that time, states would be well advised to use the time before the 2010 Census to develop strategies to adjust Census Bureau data. It is absolutely essential to our democrcy that the districts are drawn to comply with the One Person One Vote rule, with state laws on residence, and with common sense conceptions of our communities.

Methodology

This report differs from our Importing Constituents reports in other states in that our analysis is not confined only to state prisoners. Our analysis of district populations is based on the sizes and locations of adult correctional facilities as counted in Census 2000 regardless of whether they are state, local, federal, private, military or halfway houses. This methodology was necessary because of general difficulties in classifying the types of correctional facilities in Texas (especially those that confine people from multiple jurisdictions inside and outside of Texas) as well as a specific difficulty with the accuracy of how the Census Bureau labeled facilities.

This methodology has the advantage of being compatible with our Too big to ignore: How counting people in prisons distorted Census 2000 report and for including the impact of large federal and private institutions on state level redistricting. These institutions confine prisoners from all over the United States, yet the Census Bureau assigns the prisoners residence to the prison location.

The drawback to this approach is that we can only talk about where the Texas Department of Criminal Justice's prisoners come from. We are therefore unable to talk about where the people confined in federal prisons and private prisons under contract with entities outside of Texas should have been counted. Similarly, the inclusion of local jails in our data understates our finding of a diluting in urban voting strength. While large state prisons in a rural area draw mostly-urban prisoners from throughout the state, a large local jail in an urban county like Harris or Dallas would confine prisoners who are mostly from that county. This transfer of population is important in a discussion of how state-level political power is distributed within a city[16], but does not measurably impact the city's ability to advocate for itself on the state level.

About the authors

Peter Wagner is Assistant Director of the Prison Policy Initiative, an Open Society Institute Soros Justice Fellow, and a 2003 graduate of the Western New England College School of Law. Mr. Wagner is the author of "Importing Constituents: Prisoners and Political Clout in New York" (April, 2002), the first systematic state analysis of the impact of prisoner enumeration policies on legislative redistricting. He has spoken and testified at numerous national and state forums on this topic. Mr. Wagner edits PrisonersoftheCensus.org and writes a weekly fact column for the website about the varied impacts on society from miscounting prisoners.

His most recent publications are "The Prison Index: Taking the Pulse of the Crime Control Industry" (April 2004) and with Eric Lotke, "Prisoners of the Census: Electoral and Financial Consequences of Counting Prisoners Where They Go, Not Where They Come From" (forthcoming, Pace Law Review).

Rose Heyer is the GIS Analyst for the Prison Policy Initiative. She developed the Geographic Information System research strategy for the Prisoners of the Census project and consults with other organizations on the use of GIS for criminal justice reform advocacy.

Her most recent publication is, with Peter Wagner, Too big to ignore: How counting people in prisons distorted Census 2000, the first national analysis of how Census counts of prisoners distort statistics on race, ethnicity, gender and income.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a grant from the Soros Justice Fellowship Program of the Open Society Institute.

Judy Greene of Justice Strategies was very helpful in orienting our research in the myriad of incarceration types in Texas. Of course, we retain responsibility for any errors or omissions in our final analysis.

Shapefiles of the Texas legislative and congressional districts as well as the populations totals for each district were provided by the Texas Legislative Council. The names of incumbent legislators and their party affiliations were gathered from the websites of the Texas House and Senate in October, 2004. The names and party affiliations for Texas' congressional delegation was developed from the New York Times after the November 4, 2004 elections.

About the Prison Policy Initiative

The Prison Policy Initiative (PPI) conducts research and advocacy on incarceration policy. Its work starts with the idea that the racial, gender and economic disparities between the prison population and the larger society represent the grounds for a democratic catastrophe. PPI's concept of prison reform is based not only in opposition to a rising rate of incarceration, but in the search for a lasting solution to pressing social problems superior to temporarily warehousing our citizens in prisons and jails.

The Prison Policy Initiative is based in Northampton, Massachusetts. For more information about PPI or prison policy in general, visit http://www.prisonpolicy.org.

Endnotes:

[1] Mother Jones Magazine, July 2001, Debt to Society: Texas, Increasing imprisonment.

[2] Rose Heyer and Peter Wagner, Too big to ignore: How counting people in prisons distorted Census 2000, April 2004.

[3] Walker County has a Census 2000 population of 61,758, 23% of whom are incarcerated. Walker County is much larger than the 25,277 median population size for a U.S. county.

[5] Texas Department of Criminal Justice, Statistical Report 2001 and U.S. Census

[6] Texas Department of Criminal Justice, Statistical Report 2001 and U.S. Census

[7] Peter Wagner, Texas incarceration rates by race, 2001 Prison Policy Initiative, April 2004

[9] Reynolds v. Sims 377 US 533 (1964)

[10] Reynolds at 567.

[11] Wesberry v. Sanders 376 U.S. 1 (1964) at 8.

[12] Stifel v. Hopkins 477 F.2d 1116, 1121 (1973)

[13] This finding confirms Eric Lotke's earlier "quick analysis" of Texas House District 13 published in a letter to The Nation.

[14] Reynolds at 562.

[15] Harold Dutton, "An Act relating to the inclusion of an incarcerated person in the population data used for redistricting according to the person's last residence before incarceration" H.B. No. 2639 2001 Texas Session. Thanks to Will Harrell for bringing this bill to our attention.

[16] In 2000, Harris and Dallas had the 4th and 6th largest jail systems in the United States based on the average number of jail inmates held. (Bureau of Justice Statistics, Prison and Jail Inmats at Midyear 2002, table 12) In 2000, the average population of the Harris County jail system was 7,854. For a similar discussion of how this could matter within an urban area, see Peter Wagner, Legislative districts belong to the people, not the politicians, Prisoners of the Census Fact of the Week, August, 23, 2004.

Events

- April 15-17, 2025:

Sarah Staudt, our Director of Policy and Advocacy, will be attending the MacArthur Safety and Justice Challenge Network Meeting from April 15-17 in Chicago. Drop her a line if you’d like to meet up!

Not near you?

Invite us to your city, college or organization.