Census Bureau’s Report: States say Bureau not doing enough to end to prison gerrymandering

In planning for the 2030 Census redistricting data, the Bureau acknowledges calls from states to end prison gerrymandering at the source — the Census — but does not signal change.

by Aleks Kajstura, January 30, 2025

One of the main complaints from the states this decade was prison gerrymandering — a problem created because the Census Bureau incorrectly counts incarcerated people as residents of their prison cells rather than their home communities. When states use this flawed Census data to draw new districts, they inadvertently give residents of districts with prisons greater political clout than all other state residents.

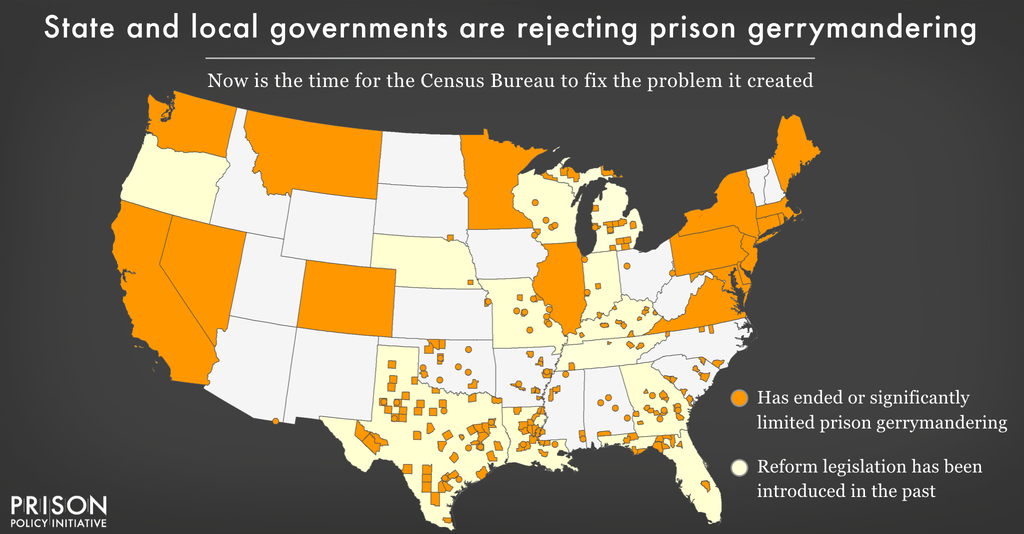

States have been tackling prison gerrymandering on their own, as the report points out: “…states representing approximately one-half of the U.S. population now have statutory or policy requirements to reallocate specific populations from where they are counted in the decennial census to an alternate location.” In plain English, that means nearly half of the US population now lives in a place that corrects redistricting data they receive from the Census to count incarcerated people at home. These include deep “blue” states like California, “purple” states like Maine and Pennsylvania, and deep “red” states like Montana — where prison gerrymandering-reform legislation received wide bipartisan support.

In this briefing, we break down the 60-page report to highlight states’ dissatisfaction with the Census Bureau for counting incarcerated people in the wrong place and examine the progress and backsliding in the way it publishes population data for correctional facilities.

States say Census’ redistricting data is no longer meeting their needs

Despite the growing number of states that are now adjusting their data to count incarcerated people at home, the Census Bureau still uses outdated notions of incarceration when deciding where incarcerated people “reside.” States made clear to the Bureau that they want this to change.

In the report, the Bureau uses circular logic to justify its flawed way of counting incarcerated people:

“Because the Census Bureau’s residence criteria, which define where the Census Bureau counts people in the decennial census, require people to be counted where they live and sleep most of the time, prisoners are counted in the facility where they are incarcerated at the time of the census.”

Even ignoring the circular nature of the Bureau’s logic, the facts do not support its interpretation of its own definition of residence. It is well-established that in the modern era of mass incarceration, incarcerated people do not “live and sleep most of the time” at the facility where they are held on any given day (including census day). Nationally, 75% of people serve time in more than one prison facility, and 12% of people serve time in at least five facilities before returning home. But even folks who stay in one place while incarcerated are only away from home temporarily; for example, in Rhode Island, the median length of stay for people serving a sentence in the state’s correctional facilities is only 99 days.

States know this and are trying to fix the issue on their own and the Census Bureau even acknowledges this effort and has provided some support to the states. As part of the 2020 Census, the Bureau expanded its tools to help states map their own address data when reallocating incarcerated people to their home communities. The Bureau reports that states “request that the Census Bureau continue this additional support.”

This help is better than nothing, but it still does not meet state redistricting data needs and the states are asking for the Bureau to count incarcerated people at home in 2030. Or as the Bureau phrased it:

States… also ask that the Census Bureau continue to look for additional support possibilities, up to and including a review/revision of where people in GQ [Group Quarters], specifically prisoners, are counted.

2020 changes to the Census were one step forward and two steps back for the states

The most useful thing the Bureau has done to help states count incarcerated people at home on their own was to publish “Table P5” as part of the official redistricting dataset. Table P5 identifies correctional facilities in Census data. In past decades, the information in this table was only available in later Census publications — often too late for states to use in redistricting.

At the same time, the 2020 Census added another wrinkle to prison gerrymandering reform by taking a new approach to its data privacy protections that unintentionally made it harder for states to adjust their redistricting data to count incarcerated people at home. Every decade, the Bureau’s privacy protections ensure that no single person can be identified in the census data and that everyone’s answers on the census forms remain private.

For the 2020 Census, the Bureau implemented a new privacy method called differential privacy, which injects “noise” into the population data published by the census. This “noise” essentially takes the correctional facility populations and adds or subtracts a statistically-determined number of people in the population data published for the census. This change may have accomplished its privacy goals but undermined states’ efforts to address prison gerrymandering because the states’ own facility populations no longer matched the populations reported by the Census.

The Bureau reports:

[The states] appreciated the Group Quarters by Type Table (P5) but requested that the Census Bureau add more detailed GQ types and add race and ethnicity characteristics to that file in 2030. They also requested the GQ total population counts and GQ type be held invariant and not be subjected to changes due to data disclosure avoidance measures.

To translate: providing Table P5 was all well and good, but then the Bureau messed with the data in a way that made things harder to decipher for the states. And so, the states are requesting that the Bureau report correct populations for the facilities. And while they’re at it, it would also be helpful to get race and ethnicity data reported for facility populations as well.

The Bureau acknowledges state needs but makes no promises

In the report, the Bureau acknowledges the states’ struggles to make its redistricting data usable by fixing it to reflect where people actually live. It said it will consider several ways to help states deal with the flawed data:

- It will continue to publish correctional facility populations as part of the redistricting dataset (the new Table P5) and increase the capacity of its address mapping tools that help the states make their own data adjustments to count incarcerated people at home themselves.

- In addition, it said it will consider adding more detail to the P5 table, such as race and ethnicity, as well as more details about the facilities themselves (for example, to differentiate between federal and state prisons or local jails).

As far as ensuring that the populations the Bureau’s reports for correctional facilities match the actual number of people they counted there on census day, the Bureau said it will keep that request in mind:

The RVDO [Redistricting & Voting Rights Data Office] is committed to keeping state liaisons informed about any discussions on Census Bureau disclosure avoidance policy changes. The RVDO also recognizes the states’ desire to hold county populations (especially those counties with small populations) invariant and GQ population counts, particularly prisons and college GQs, invariant at the block level and will ensure those requests are part of the discussion.

The Bureau also said that they will once again review the residence rule to determine whether they should count incarcerated people at home. But, considering the Bureau’s history of stubbornly clinging to its outdated way of counting incarcerated people, change is certainly not guaranteed.

States need to prepare to fend for themselves once again for the 2030 Census

In this report, the Bureau gave no indication of whether it is taking steps to count incarcerated people at home in 2030. While we hope that changes, states shouldn’t wait for the federal government to make up its mind. They should take action now to ensure their next redistricting process accurately reflects the makeup of their state.

States that have not yet passed legislation to end prison gerrymandering need to do so soon. This will ensure the state’s Department of Corrections can collect the data needed to successfully count incarcerated people at their home addresses. Our model bill is a great place to start. It provides clear guidance on how this data should be collected, by whom, and how it will be used for the redistricting process.

The View from the States report makes clear that states recognize the Census Bureau’s way of counting incarcerated people is flawed and outdated. What’s less clear is whether the Bureau will listen to the calls for change. Considering the Bureau’s past feet-dragging on this issue, states should take steps now to ensure their democracy is protected from prison gerrymandering, regardless of what the federal government chooses to do.