Too big to ignore:

How counting people in prisons distorted Census 2000

By Rose Heyer and Peter Wagner

Prison Policy Initiative

April 2004

Section:

Impact on county size

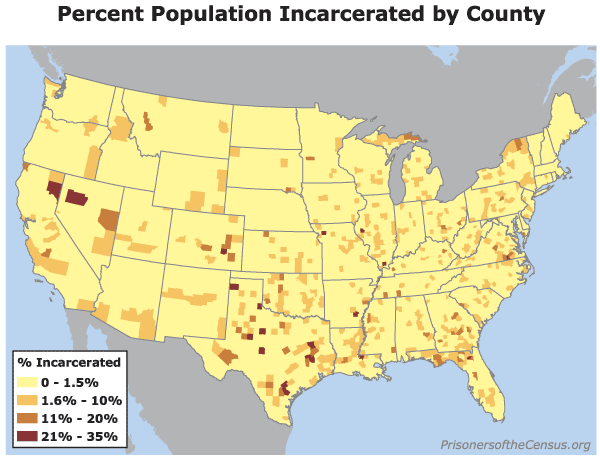

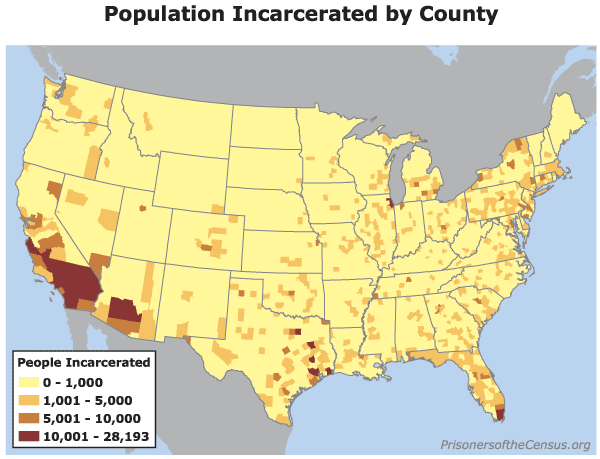

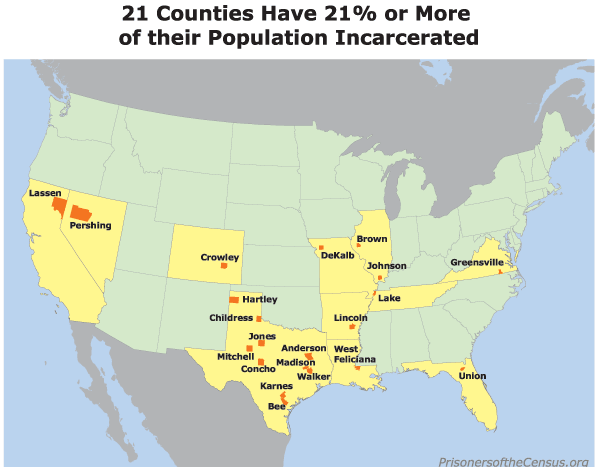

Counting large external populations of prisoners as local residents leads to misleading conclusions about the size and growth of communities. Many of the prison hosting counties have relatively small actual populations, but large prison populations. Twenty one counties in the United States have at least 21% of their population in prison. (See Figures 5, 6 and 7.)

The Census Bureau’s 2002 estimates show that Ohio’s troubled Mahoning County lost 4,250 residents since the Census. Yet almost half of that loss is explainable by the closure of a large private prison in Youngstown.[7]

Growth, too, may also be artificial. The Census Bureau’s 2002 estimates reported that Brent, Alabama was the second fastest growing town in the state. The 900 men added to the existing facility accounted for the entire population growth in the town. Bibbs County, which contains Brent, was labeled the second fastest growing county in the state but its actual growth was negligible. In Alabama, 30 out of 67 counties are losing population, so a county that reports a growing population will appear to be more economically successful. The impact of prisoners propelling Brent from the middle to the top of the Alabama pack was not noted in the Census Bureau’s data or in initial press coverage. The Birmingham News discovered the quirk because “a skeptical Birmingham News reader in Centreville alerted the newspaper to Brent’s prison boom.”[8]

Regional statistics are also subject to hidden distortion as Rolf Pendall of the Brookings Institution discovered. Upstate New York was one of the slowest growing regions in the country, growing only 1.1 percent from 1990 to 2000. But things were even worse than they appeared:

“Almost 30 percent of new residents who came to Upstate New York in the 1990s didn’t make the trip by choice, and they didn’t move into subdivisions or houses on secluded cul-de-sacs. They were inmates making their new homes in prison cells.”[9]

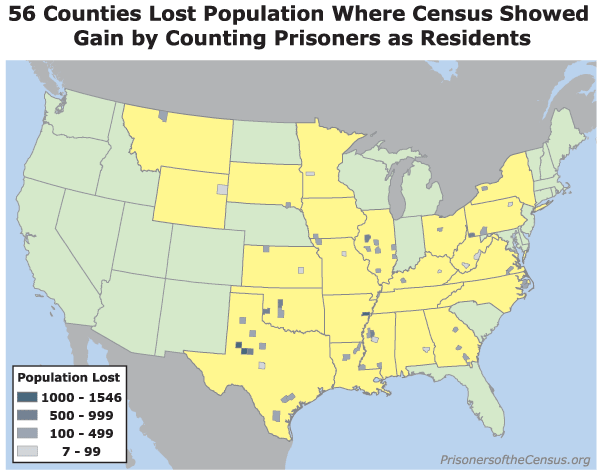

Counting the incarcerated population can make counties with declining populations appear to be growing. Census 2000 reported that 78% of counties experienced population growth during the 1990s. Yet 56 of these counties can attribute their growth only to prison expansion and not to children being born or new residents choosing to move to the county. Said another way, for each 50 counties labeled by the Census as growing during the 1990s, one of those counties actually saw a decline in their actual free population. (See Figure 7.)

Figure 5. Many counties show a large percentage of their population consists of prisoners imported from elsewhere.

Figure 6. Many counties report large numbers of incarcerated residents. Outside of urban counties with large jails, these populations consist primarily of prisoners placed in the county by state or federal authorities.

Figure 7.

Figure 8. Census 2000 reported how many counties grew during the 1990s and how many declined. But if not for the construction of new prison cells, 56 counties labeled as growing would have reported declining populations.

Footnotes

[7] JoAnne Viviano, Valleys are still losing people, The Vindicator (Youngstown, Ohio) July 14, 2003 and Peter Wagner, Counting prisoners as prison-town residents leads to “misleading” conclusions about growth, PrisonersoftheCensus.org Fact of the Week for August 4, 2003.

[8] Jeff Hansen, Brent is booming, behind iron bars, Birmingham News, July 18, 2003 and Peter Wagner, Counting prisoners as prison-town residents leads to “misleading” conclusions about growth, PrisonersoftheCensus.org Fact of the Week for August 4, 2003.

[9] Erika Rosenberg, Upstate’s outlook mostly murky, Democrat and Chronicle (Rochester, NY) August 24, 2004. and Rolf Pendall, Upstate New York’s Population Plateau, The Brookings Institution. August 2003.

Events

- April 15-17, 2025:

Sarah Staudt, our Director of Policy and Advocacy, will be attending the MacArthur Safety and Justice Challenge Network Meeting from April 15-17 in Chicago. Drop her a line if you’d like to meet up!

Not near you?

Invite us to your city, college or organization.