Too big to ignore:

How counting people in prisons distorted Census 2000

By Rose Heyer and Peter Wagner

Prison Policy Initiative

April 2004

Section:

Impact on gender statistics

Given that 92% of the people in prisons and jails are men, including these populations as local residents can create a large hidden shift in gender and marriage data used for planning social services and future growth.[11]

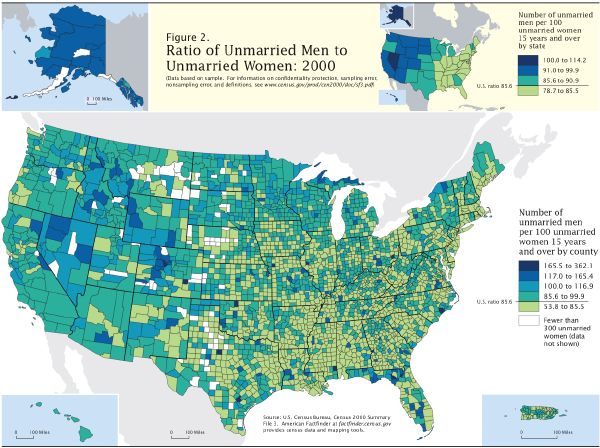

Nationally, there are 86 unmarried men for every 100 unmarried women in the United States.[12] The ratio will vary between neighborhoods, cities, regions and states from a variety of influences. Some are the reflection of women's greater longevity compared to men, different cultural ideas about marriage, and some are the result of social and economic demographics like the concentration of young people in particular areas. (See Figure 15.)

The disparity between states is somewhat small, ranging from Alabama and Rhode Island at 79 unmarried men to 100 unmarried women, to Alaska at 114 unmarried men per 100 unmarried women. (Alaska is a very small state that has many industries that rely on imported male workers. The next state is Nevada at 103 unmarried men per 100 unmarried women.)

Unlike the state to state disparity, the county disparity is huge, ranging from 53.8 to 362 unmarried men per 100 unmarried women. While relatively useful for some purposes on the state level, this data is more difficult to use on the county or town level because the Census includes "special populations" of prisoners and soldiers -- which tend to be male -- in with the local community rather than at their actual homes.

A report in Ohio's Fremont News Messenger is typical of the problems that this data can create and of the limited options researchers have to fix it. Analyzing the Census Bureau's Marital Status 2000 report, the News Messenger found that of the 5 Ohio counties identified by the Census as containing more unmarried men than unmarried women, all 5 of these counties contained large prisons.

The News Messenger article focused on the data less for its policy implications than as a human interest story about the best places to be single and dating. Yet the difficulties experienced by the News Messenger are illustrative. Reporter Greg White was able to manually correct for the prison-effect in rural prison counties by subtracting the prisoner population, but he could only guess the impact in urban communities where most prisoners originate:

Even if a county has a prison, that does not hinder dating prospects for most women [because the true number of men is unchanged by the presence of the prison], said Carol Getty, who teaches criminal justice at Park University in Parkville, Mo. The biggest problem comes in some urban neighborhoods where up to half of men in their late teens and 20s may be in prison.[13]

If the Census counted prisoners at their home addresses, the whole exercise of correcting the data for actual use would be moot, and the data would be more useful.

Figure 15. Many counties (in darkest blue) report having more than double the U.S. average ratio of unmarried men to unmarried women. In many of these counties, the origin of the disparity is the inclusion of large male prisons as a part of the county's statistics. (Map source: U.S. Census Bureau, Marital Status 2000.)

Footnotes

[11] "Planning and implementing many government programs calls for accurate information on marital status, including the numbers of employed married women, elderly widows living alone, and single young people who may soon establish homes of their own. Data about marital status are used for budget and resource planning to identify the number of children needing special services, such as children in single-parent households. Local governments need data about marital status to assess the need for housing and services under Community Development Block Grant Evaluation. Other examples of statutory applications include the Public Health Service Act, Child Welfare Act, Adolescent Family Life Projects, and Low-Income Tax Credits." Census Bureau, Marital Status 2000, pp. 11-12.

[12] Census Bureau, Marital Status 2000, page 7.

[13] Greg Wright, Where the boys are -- behind bars, Fremont News Messenger (Ohio), October 22, 2003.

Events

- April 15-17, 2025:

Sarah Staudt, our Director of Policy and Advocacy, will be attending the MacArthur Safety and Justice Challenge Network Meeting from April 15-17 in Chicago. Drop her a line if you’d like to meet up!

Not near you?

Invite us to your city, college or organization.