Actual Constituents: Students and Political Clout in New York

By Peter Wagner

Prison Policy Initiative

October 6, 2004

Introduction

In New York and around the country, county election officials frequently attempt to deny college students the right to vote in local elections under the incorrect and unconstitutional theory that a dorm is not a residence. In some counties, officials attempt an outright ban on student voting[1], in others the students are subjected to burdensome forms not imposed upon other voters, and in other counties the students are encouraged to vote somewhere else. While the attempt to disenfranchise students is common, occurs in other parts of the country, and dates back decades, the practice almost never survives challenge by civil rights attorneys and the courts. At a time when state legislators in New York are up for reelection, one critical question has gone unasked: Whose districts are these?

This report draws on our experience studying how another special population affects the uniquely American democratic system of state legislatures to make a new argument why college students should be allowed to vote in local elections. This report will focus on the numbers in New York state to tell a national story about how state legislative districts are drawn, why they are drawn to contain equal numbers of people, and why it makes good sense to include students at their college addresses as a part of legislative districts.

This report explains how our democracy works and why students should be welcomed at the polls. Students must be allowed to vote locally because the state legislative districts in which they reside belong just as much to them as to anyone else who lives there.

How our government works -- Redistricting 101

By state constitution and U.S. Supreme Court precedent, all states are required to redraw state legislative districts every 10 years to keep the districts of equal population size and thereby ensure that each citizen's vote is of equal weight. The ideal district size is determined by taking the state's new population total in the U.S. Census and dividing it by the number of seats in that legislative chamber.

After the 2000 Census, each district in the New York State Assembly was supposed to contain 126,510; and each district in the State Senate 306,072 people. Keeping the old districts would not be possible as the population change was not even throughout the state. In the eight years between when the old districts were drawn in 1992 and the 2000 Census, the most populous New York Senate district had grown to have 98,949 more people than the smallest. In that same time period, the most populous New York Assembly district grew to have 60,720 more people than the least populous.[2]

Armed with the Census data, the legislature establishes a taskforce each decade to adjust the boundary lines of each district so that it contains the required number of people. By the federal constitution, the legislature is allowed only a small deviation from strict population equality in each district.

The basic principle of American representative democracy is that every vote must be of equal weight. This is known as the "One Person One Vote" rule and originates in the landmark 1964 Supreme Court case Reynolds v. Sims[3]. Voters in two urban Alabama counties sued because the existing legislative districts were based on counties and not population. There was a huge difference in population sizes, with the largest district having 41 times the population of the smallest. Believing the situation in Alabama to be illustrative of a large number of other states drawing legislative boundaries in such a way as to dilute the political power of citizens based on where they lived, the Supreme Court wrote a very broad opinion to guide the states in fairly apportioning the state legislatures.

If districts are of equal size, each citizen has equal access to a representative to advocate for her or his needs. When districts are of substantially different sizes, the weight of each vote starts to differ. In under-populated districts, each vote is worth more, and in overpopulated districts, a vote is worth less. In 1960 Alabama, a Lowndes County senator had the same political power as one from Jefferson County with 634,864 people, but the Lowndes County senator could devote her or himself to advancing the interests of only 15,417 people. As a result, a vote in Lowndes county was worth over 41 times a vote in Jefferson county. Reynolds v. Sims barred this practice and put it plainly: "[T]he weight of a citizen's vote cannot be made to depend on where he lives."[4]

In order to ensure that each district will be of equal population size, the legislature must adjust the lines of each district so that it will contain the proper number of people. If each Assembly district in New York state has 126,510 people, then each person in the state will have the same access to the legislative decision making process.

And our town's population is ... Ask the Census

Since 1950, the Census Bureau has counted students as residents of their college town. This makes sense for a number of reasons.

First, students need to be counted somewhere. College students are at the college at least 8 months a year and there is no predicting whether the students will stay in the college town, visit their parents, or go elsewhere to work during the summers.

Second, the students willingly go to the college town. While some colleges are more economically and socially self-reliant than others, in most college communities the students are a part of the larger community's social and economic life. Local businesses welcome the students. Long-time residents rent apartments and sell products to students and they hire the students part-time to help run their businesses. Students become a part of the community that surrounds their on and off-campus residences.

Third, it doesn't matter that the majority of the students don't intend to remain in the college town forever. They intend to remain for the time being. That is not only the legal definition of residence, it matches the actual practice of the rest of the community whose voting rights are not being challenged. The modern United States is a nation of migrants. According to the Census, 45% of Americans moved in the last half of the 1990s.[5]

One of the first influential cases to hold that a college student was a local resident was a Supreme Court of New Jersey case that addressed many of these issues. Remarking that it once held a contrary opinion, the Court explained what had changed:

"These statements [in our previous cases] were made in relatively immobile eras when it was generally assumed that the college student would lead a semi-cloistered life with little or no interest in noncollege community affairs and with the intent of returning, on graduation, to his parents' home and way of living. Such assumption of course has no current validity."[6]

This Supreme Court of New Jersey case recognized a changing world, but it is not a new decision. Justice Jacobs wrote the opinion long before today's college students were born: in 1972.

More than thirty years later, the trends he recognized are even more true. It makes perfect sense for the U.S. Census to include college dorm students in the population totals for the towns that contain the dorms, and local registrars need to accept these facts.

Students should tell local registrars: Whose districts? Our districts.

The One Person One Vote rule gives each person equal access to government. Equally sized legislative districts give each resident an equal ownership stake in their legislature. Colleges students boost the town's population and its political clout but local Board of Elections commissioners turn democratic principles upside down when they deny these same students the right to vote.

The college dorm population is not insignificant in many districts. In 11 Senate and in 18 Assembly districts, more than 2% of the district's population is students in dorms. One district is more than 10% students living in dorms. (See Tables 1 and 2, and Maps 1 to 3)

Students living in dorms at Ithaca College, Cornell University and SUNY Cortland make up more than 10% of Assembly District 125, represented by Barbara Lifton (D). Oneida County made headlines last year for trying to keep Hamilton College sophomore Young Han from voting locally.[7] The 1,600 students in Han's district (Number 115, represented by Republican David R. Townsend) make up 1.25% of the district.

In neighboring Madison County, students aren't barred from voting, rather the County just discourages students from voting locally.[8] Talking about the Madison County districts is complicated by the fact that the county population is small and the districts include towns and college dorms in other counties. But Madison County is in Assembly District 111, Represented by Bill Magee (D), which is 5.64% students. Madison is in Senate District 49, represented by Nancy Hoffman (R), a district that is 3.65% students living in dorms.

These are not inconsequential numbers. These dorm populations are helping to make the district what it is.[9] Without the dorm population, the districts would be very different and the county would have less political clout in the state legislature. Since the students helped give the county its rightful share of the state's political power, shouldn't the county give all of the district's constituents the same right to determine its future?

| District Number | Name of Assemblyperson (Jan 2003) | Party of Legislator (Jan 2003) | District Population, 2000 | Dorm population, 2000 | Percentage of district population that is students in dorms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 125 | Barbara S. Lifton | Democratic | 125,447 | 13,110 | 10.45% |

| 66 | Deborah J. Glick | Democratic | 128,091 | 9,109 | 7.11% |

| 69 | Daniel J. O'Donnell | Democratic | 128,053 | 8,501 | 6.64% |

| 111 | Bill Magee | Democratic | 127,962 | 7,211 | 5.64% |

| 130 | Joe Errigo | Republican | 126,482 | 7,080 | 5.60% |

| 147 | Daniel J. Burling | Republican | 125,572 | 6,994 | 5.57% |

| 104 | John J. McEneny | Democratic | 128,373 | 6,811 | 5.31% |

| 118 | Darrel J. Aubertine | Democratic | 128,234 | 6,202 | 4.84% |

| 120 | William B. Magnarelli | Democratic | 128,805 | 5,701 | 4.43% |

| 102 | Joel M. Miller | Republican | 129,098 | 5,506 | 4.26% |

| 126 | Robert J. Warner | Republican | 130,213 | 5,090 | 3.91% |

| 148 | James P. Hayes | Republican | 125,055 | 4,817 | 3.85% |

| 131 | Susan V. John | Democratic | 126,274 | 3,566 | 2.82% |

| 18 | Earlene Hooper | Democratic | 131,139 | 3,427 | 2.61% |

| 106 | Ronald J. Canestrari | Democratic | 128,373 | 2,810 | 2.19% |

| 144 | Sam Hoyt | Democratic | 131,862 | 2,813 | 2.13% |

| 114 | George Christian Ortloff | Republican | 132,349 | 2,816 | 2.13% |

| 78 | Jose Rivera | Democratic | 121,111 | 2,442 | 2.02% |

| District Number | Name of Senator (Jan 2003) | Party of Legislator (Jan 2003) | District Population, 2000 | Dorm population, 2000 | Percentage of district population that is students in dorms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 53 | John Randy Kuhl, Jr. | Republican | 294,378 | 12,170 | 4.13% |

| 29 | Thomas K. Duane | Democratic | 311,260 | 11,842 | 3.80% |

| 49 | Nancy Larraine Hoffmann | Republican | 291,303 | 10,620 | 3.65% |

| 55 | Jim Alesi | Republican | 301,947 | 10,411 | 3.45% |

| 46 | Neil D. Breslin | Democratic | 294,565 | 9,037 | 3.07% |

| 30 | David A. Paterson | Democratic | 311,263 | 8,029 | 2.58% |

| 51 | James L. Seward | Republican | 291,482 | 7,414 | 2.54% |

| 57 | Patricia K. McGee | Republican | 295,288 | 7,416 | 2.51% |

| 47 | Raymond A. Meier | Republican | 291,303 | 6,953 | 2.39% |

| 41 | Stephen M. Saland | Republican | 301,528 | 6,403 | 2.12% |

| 2 | John J. Flanagan | Republican | 305,990 | 6,343 | 2.07% |

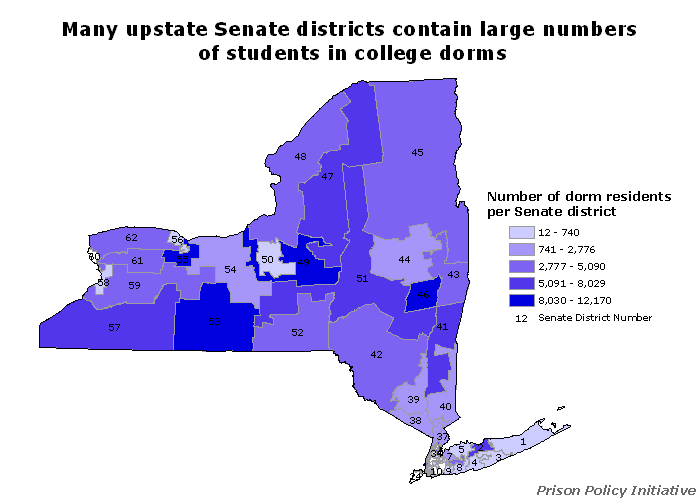

This map shows were the Census counted dorm populations of various sizes in New York State.

New York State Assembly districts are drawn to contain about 126,510 people in each district. This map takes the dorm populations shown in the first map and colors each state Assembly district to show the number of students in dorms in each district.

New York State Senate districts are drawn to contain about 306,072 people in each district. This map takes the dorm populations shown in the first map and colors each Senate district to show the number of students in dorms in each district

That other special population -- prisoners

Voting rights activists have been fighting for over 30 years to enforce court decisions upholding a student's right to a voting residence in a college dorm. Now another issue has emerged around another "special population" that is counted as residents of the place they sleep: state and federal prisoners.

In 2000, New York State had 71,466 state prisoners, 43,740 of whom are from New York City. Ninety-one percent of the state's prisoners are incarcerated in upstate legislative districts. In an analysis methodologically similar to this report, we reported in Importing Constituents: Prisoners and Political Clout in New York, [10] that in three New York Senate districts and in ten Assembly districts more than 2% of the "constituents" are in prison. The two strongest proponents of incarcerative policies in the state Senate are upstate Republican Senators Volker and Nozzolio, heads of the Committees on Codes and Crime, respectively.[11] Going in to the 2002 redistricting, we found that the prisons in their two districts held more than 23% of the state's prisoners.[12]

The most troubling aspect of miscounting prisoners in this fashion is the potential to change the balance of political power between communities who stand on opposite ends of state crime control policy. Taking electoral clout from urban communities which are the most negatively affected by aggressive incarceration policy, and giving that clout to rural communities that benefit from prison jobs has the potential of launching a cycle of prison growth without a democratic restraint.

However, counting students as residents of the college town does not similarly dilute voting strength because students are allowed -- despite some errant county officials -- to vote locally. In 48 states, prisoners are barred from voting.[13] In Maine and Vermont, where prisoners are allowed to vote, and in Massachusetts and Utah were prisoners were allowed to vote as recently as the 1990s, prisoners were required to vote via absentee ballot back home.[14] If prisoners are once again allowed to vote in New York, there is no question that the state constitution will require them to vote via absentee ballot back home.

The growing movement to have the Census Bureau change how it counts the incarcerated is not the first time that people have questioned where prisoners actually reside and then concluded they reside at home. Most states have constitutional clauses or statutes that define residence for incarcerated people to be the place they lived prior to incarceration. Similar rules exist in other contexts, such as determining where a person may file a lawsuit. But no one has summarized the rule and its rationale as clearly as Judge Wade H. McCree did in a 1973 decision:

It makes eminent good sense to say as a matter of law that one who is in a place solely by virtue of superior force exerted by another should not be held to have abandoned his former domicile. The rule shields an unwilling sojourner from the loss of rights and privileges incident to his citizenship in a particular place....[15]

As Table 3 illustrates, students and prisoners are very different populations. While the Census Bureau's count of students at the college address is consistent with modern ideas of residence, the Bureau's method of counting prisoners is incompatible with modern democracy.

| Students | Prisoners | |

|---|---|---|

| In college/prison town by choice | Yes | No |

| Has control over whether to transfer to another institution | Yes | No |

| Can vote | Yes | In 48 states, No (only in Maine and Vermont) |

| By Supreme Court precedent, can vote locally | Yes | No |

| Encouraged to leave the institution to spend money locally | Yes | No |

| Has interactions with surrounding community | Yes | No |

| Is welcome to stay in local community upon graduation/release | Yes | No |

| Odds of returning to pre-college or pre-prison address after graduation/release | Low | High |

Conclusion

Student populations are a large boost to the population and economy of New York's upstate region. This population helps make the region what it is socially and economically. Because, as they should be, students are counted in the Census at their college addresses, the students also help make the region what it is politically as well. Discouraging or outright denying students the right to vote for the legislators who represent them violates all of the democratic principles that we hold dear.

About the author

Peter Wagner studies census policy, redistricting and barriers to the democratic process at the Prison Policy Initiative, a research and advocacy organization in Northampton Massachusetts. He is Assistant Director, an Open Society Institute Soros Justice Fellow, and a 2003 graduate of the Western New England College School of Law.

Mr. Wagner is the author of "Importing Constituents: Prisoners and Political Clout in New York" (April, 2002), the first systematic state analysis of the impact of prisoner enumeration policies on legislative redistricting. He has spoken and testified at numerous national and state forums on this topic. Mr. Wagner edits PrisonersoftheCensus.org and writes a weekly fact column for the website about the varied impacts on society from miscounting prisoners.

His most recent publications are "The Prison Index: Taking the Pulse of the Crime Control Industry" (April 2004) and with Eric Lotke, "Prisoners of the Census: Electoral and Financial Consequences of Counting Prisoners Where They Go, Not Where They Come From" (forthcoming, Pace Law Review).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a grant from the Soros Justice Fellowship Program of the Open Society Institute.

About the Prison Policy Initiative

The Prison Policy Initiative (PPI) conducts research and advocacy on incarceration policy. Its work starts with the idea that the racial, gender and economic disparities between the prison population and the larger society represent the grounds for a democratic catastrophe. PPI's concept of prison reform is based not only in opposition to a rising rate of incarceration, but in the search for a lasting solution to pressing social problems superior to temporarily warehousing our citizens in prisons and jails.

This report draws on the Census mapping skills and legal research developed for our Prisoners of the Census project, which seeks to quantify, publicize and reform the current practice of utilizing the Census to shift political power away from poor and minority communities and into the hands of prison expansion proponents. In that work identifying where prisoners come from, where they go and why redistricting matters, we were often asked about college students. We are glad to have this opportunity to explain why we think the Census Bureau is right to count students in college dorms but wrong to count prisoners in their cages.

The Prison Policy Initiative is based in Northampton, Massachusetts. For more information about PPI or prison policy in general, visit http://www.prisonpolicy.org. For more information about how the Census Bureau's method of counting prisoners as residents of the rural towns that host prisons dilute urban and minority voting strength, visit http://www.PrisonersoftheCensus.org

Methodology

Because dorm populations are the most controversial and because students living in private housing may commute to the college an unknown distance from their homes, this report focuses only on the dorm populations as counted in the U.S. Census. The actual student population of each district is therefore considerably higher than the dorm populations discussed in this report. However, many of the same Census counting and right to vote questions also apply to college students that do not live in dorms.

Census Bureau data does not distinguish between students living in private private off-campus housing and non-students living in private housing. While we considered using the Department of Education's data on how many students were enrolled at each college and university to account for off-campus students, we would not have been able to reliably place those students in to particular legislative districts. For these reason the study focuses on college dorm populations rather than the larger universe of college students.

This report takes the college dorm population as counted by Census 2000 and overlays it over the districts drawn by the New York State Legislative Task Force on Demographic Research and Reapportionment in 2002. These maps and district information were published on the internet by the Empire State Development, State Data Center. We identified individual census blocks of dorm populations as belonging to particular college by a variety of means, including a shapefile distributed by the New York State Education Department.

Endnotes:

[1] This does not currently happen in New York. In 2003, until lawyers intervened, Oneida County refused to let Hamilton College Sophomore Young Han vote locally, requiring him to vote absentee at his parent's home. See Damien Cave, Mock the Vote, Rolling Stone, May 5, 2004.

[2] The 2000 populations of the 1992 districts are available in Peter Wagner, Importing Constituents: Prisoners and Political Clout in New York, Tables 8 and 9, (Prison Policy Initiative, 2002) available at http://www.prisonpolicy.org/importing/.

[3] Reynolds v. Sims 377 US 533 (1964).

[4] Reynolds at 567.

[5] U.S. Census 2000, Summary File 3, Table P24. Accessed October 2, 2004. This important point was, to my knowledge, first made in Megan Tady, Banning the Vote, Alternet May 23, 2004.

[6] Worden v. Mercer County 61 N.J. 325 (1972).

[7] Damien Cave, Mock the Vote, Rolling Stone, May 5, 2004.

[8] Saba Ali, College students push to get out vote, The [Syracuse, NY] Post-Standard, September 21, 2004.

[9] For a detailed discussion of how including or not including a special population would change how specific district lines are drawn, see an example about prisoners: Peter Wagner, How prison counts affect state districting boundary lines, Prisoners of the Census.

[10] Peter Wagner, Importing Constituents: Prisoners and Political Clout in New York (Prison Policy Initiative, 2002).

[11] Editorial, Full-Employment Prisons, N.Y. Times, Aug. 23, 2001, at A18.

[12] These figures were somewhat lower after the 2000 redistricting, because the large increase in the prisoner population during the previous decade, forced these legislators to "share the wealth" with their neighboring but non-prison hosting districts.

[13] Peter Wagner, States that disenfranchise persons in prison, Prison Policy Initiative Atlas, January 2004.

[14] Peter Wagner, If prisoners could vote, they would vote at home, not in the prison town, Prisoners of the Census Fact of the Week, December 15, 2003.

[15] Stifel v. Hopkins 477 F.2d 1116, 1121 (1973).

Events

- April 30, 2025:

On Wednesday, April 30th, at noon Eastern, Communications Strategist Wanda Bertram will take part in a panel discussion with The Center for Just Journalism on the 100th day of the second Trump administration. They’ll discuss the impacts the administration has had on criminal legal policy and issues that have flown under the radar. Register here.

Not near you?

Invite us to your city, college or organization.