by Peter Wagner,

February 16, 2004

The legislative districts in St. Lawrence County average 7,462 residents in size. District 2 (Ogdensburg) counts 2,074 prisoners in two state prisons as “residents”; District 5 (Gouverneur) includes 1,046 prisoners. None of the prisoners are allowed to vote, and few, if any, are from St. Lawrence County. The votes of 5,639 county residents in District No. 2 have been given the same weight as 7,462 residents in other districts. This is the same as pretending that the votes of 8 people are equal to the votes of 10. Is the principle of “one person one vote” violated when 8 votes are considered equal to 10?

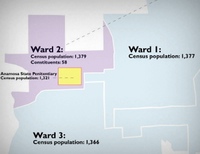

State legislatures are not the only places where democracy is distorted by including prisoner populations in the redistricting data. Counties are also required to redistrict their legislatures (or Boards of Supervisors) after each Census. Although prison hosting communities do not see the prisoners as local residents, the Census chooses to count prisoners as if they were. This creates an interesting problem, as illustrated by adjoining rural counties in upstate New York that treat the prison counting issue in different ways.

St. Lawrence County recently changed policy and counted 3,120 prisoners in their local redistricting plan. The population of one legislative district there is more than one-quarter prisoners. Although the legislative districts average 7,462 county residents, District #2 in Ogdensburg has only 5,639. This gives the residents of District 2 unequal voting power over other county residents.

Franklin, a similar county, neighbors St. Lawrence to the east. Franklin County has always excluded the prison population and has just done so again. This policy avoids what is believed in Franklin County to be an absurd result: A single district (near the Village of Malone) with a population that is two-thirds prisoners. In such a district, actual county residents would have triple the voting power of other county residents.

Prisoners are not allowed to vote. They aren’t allowed to enter the town to participate in it. Their presence is temporary and at the discretion of the Department of Correctional Services. When their sentences expire, or the prison decides to move them, the prisoners will be gone.

As these two counties illustrate, relying on U.S. Census data is not a guaranteed way to establish legislative districts which comply with the one person one vote principle.