Three ways to fix Census counting problem

by Peter Wagner, May 17, 2004

I was recently asked if restoring a prisoner’s right to vote would solve the census counting problem. Personally, I think that would be a good idea, but it would not address the principal problem from miscounting the incarcerated: diluting the votes of prisoners’ home communities.

All states that allow or recently allowed prisoners to vote required them to do so back home via absentee ballot. Most states have constitutional clauses or statutes that say that incarceration does not change a residence. (See for example New York, Arizona, Michigan, Vermont and Maine.) If prisoners were to be allowed to vote, it would be back home. Letting prisoners vote is controversial. Where they would vote is not.

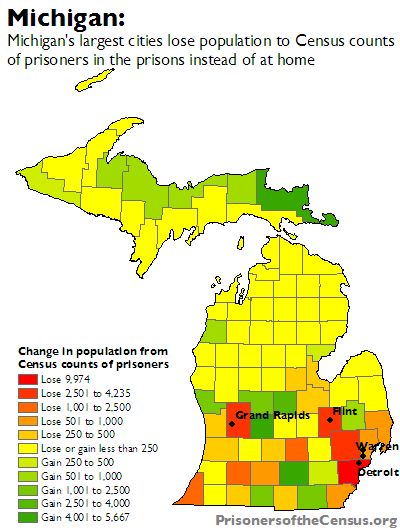

The real victims from the way the Census counts prisoners are prisoners’ family and neighbors — people who have not been convicted of anything. Counting the incarcerated not at their homes but in radically different communities dilutes the votes of all the residents of the home communities.

There are 3 potential solutions:

- The Census Bureau can change its “usual residence rule” to count prisoners at the address they declare or at their last known address. The Census wrote the rules and they can change them. In the past, the Census has changed how numerous groups were counted, including college students, missionaries, and overseas Americans.

- States can fix the Census data before conducting redistricting. New York fixed some Census Bureau mistakes that placed some prisons in the wrong rural county. Kansas’ constitution requires that out-of-state students and military be deducted and in-state students and military restored to their homes. The Kansas Secretary of State sends out a survey to the colleges and military bases, and then fixes the data before giving it to the Legislature for redistricting.

- States can do their own censuses. Many states used to do this. Massachusetts was the last to abolish the state census, in about 1990. New York’s Constitution talks about bringing back the state census if the federal census does not contain the necessary data. Counting prisoners in the wrong part of the state sounds like deficient data to me.

The best solution is the first one. The Census should just update the usual residence rule to count the incarcerated at home. The rule might have made sense in 1790 when incarceration was low and redistricting didn’t exist, but it’s a relic now.