by Peter Wagner,

June 28, 2004

In 1894, Michael Cady tried to register to vote using his address at the Tombs Jail in New York City. Jail inmates are allowed to vote, but he was convicted for illegal registration because the NY Constitution says that

“no person shall be deemed to have gained or lost a residence, by reason of his presence or absence … while confined in any public prison.”

The prosecution’s theory was that while Cady was allowed to vote, he could not vote in the prison district. Even though Cady was planning on staying at the Tombs forever, Cady must have — the prosecution argued — lived somewhere else before.

The highest court in New York agreed:

“The Tombs is not a place of residence. It is not constructed or maintained for that purpose. It is a place of confinement for all except the keeper and his family, and a person cannot under the guise of a commitment … go there as a prisoner, having a right to be there only as a prisoner, and gain a residence there.”

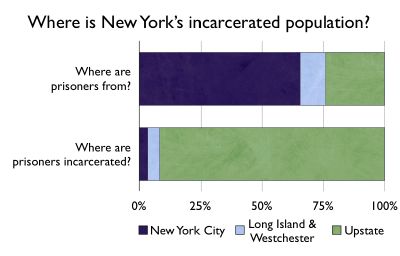

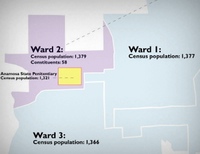

When counting the population of each state, the federal Census counts the nation’s mostly urban prisoners as if they were residents of the rural towns with the prisons. When the Census first started in 1790 with the purpose of dividing Congressional seats among the states, that probably made sense. But today one of the biggest users of Census data is state legislatures that must redraw their legislative districts each decade to comply with the Supreme Court’s “One Person One Vote” rule of equally sized districts. Relying on the Census Bureau to count the population sounds convenient and fair, but until the Census Bureau changes how it counts prisoners, using the federal Census data might not be the best way to insure that districts comply with the requirements of the 14th Amendment and how many state constitutions define residence.

If calling your jail cell your residence gets you sent to prison, shouldn’t it also be illegal for rural legislators to call prisoners their “constituents”?

Read more about Michael Cady in Importing Constituents: Prisoner and Political Clout in New York.