Jessica Pupovac of Illinois Issues covers Illinois efforts to end prison-based gerrymandering.

by Andrew Adams,

March 16, 2011

As the Census Bureau was just beginning its count last year, State Rep. LaShawn Ford, a Chicago Democrat, sponsored a bill to correct prison-based gerrymandering in Illinois.

As the Census Bureau was just beginning its count last year, State Rep. LaShawn Ford, a Chicago Democrat, sponsored a bill to correct prison-based gerrymandering in Illinois.

Jessica Pupovac, in a February 2010 article in Illinois Issues, wrote that:

50,000 prisoners throughout Illinois will be counted at [prisons located] in communities where they are unlikely to ever cast a ballot, send a child to school or access social services.

Now, a year later with the census complete, Rep. Ford’s bill is again live in the House.

Pupovac interviews U.S. Census Bureau’s Jim Dinwiddie who explains, “We’ve been doing that the same way since 1790.”

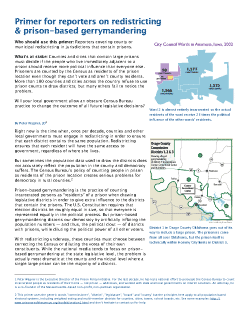

The Census Bureau has always counted prisoners at the location of the prison, but only recently in the era of mass incarceration has this effected legislative districts. For example, Lee County is comprised of four districts, each containing about 9,000 people. But the population of one of Lee’s districts is 25% prisoners. 75 voters in the district containing the prison have the same voting power as 100 voters in the other districts.

Nonetheless, Dinwiddie told Pupovac:

The main thing is that everybody understands this is how we do it, and then they can interpret the data the way they interpret the data. States may want to look at how they do their districting or fund allocation within the state. Maybe they want to exclude populations…. That’s up to them.

So Rep. Ford’s proposed legislation is fine with the Census Bureau. In fact, Pupovac tells us that, “At least seven counties in Illinois – Logan, Christian, LaSalle, Livingston, Crawford, Fulton and Knox – have taken it upon themselves to tweak their population figures so that prison populations simply aren’t included in city and county districting.”

Illinois courts have already said that an inmate isn’t a resident of the prison.

Moreover,

Illinois courts have already said that an inmate isn’t a resident of the prison. County of Franklin v. County of Henry, take this obvious point and make it explicit: “a person confined in prison under the judgment and sentence of a court does not thereby change his residence.”

41% of Illinois’ 50,000 inmates are from Chicago’s Cook County, but 90% of these inmates are incarcerated downstate. As Pupovac points out:

In 20 Illinois counties, more than half of the black population reported in the census as local residents are in fact incarcerated people from elsewhere in the state.

And

95 percent of the state and federal prison cells are located in disproportionately white counties.

Rep. Ford points out what many are already thinking:

You have to have good representation for all people in government.

It erodes minority influence in government.

You have to have good representation for all people in government. That’s why it’s there. And if you don’t have everyone represented, then it’s not a good representative government.

Who would oppose such sensible legislation? Pupovac’s article points to State Rep. John Cavaletto, a Republican from downstate Salem whose district includes a prison population of about 3,500 prisoners.

Cavaletto offers two reasons to ignore existing state law and oppose Rep. Ford’s legislation. First, Cavaletto argues that counting incarcerated people in their home communities is “nothing more than a grab for representation.”

The real grab for representation is in Cavaletto’s district. Their votes have more power than their neighbors in other rural districts that don’t contain a prison.

The bill does not apply to federal or state funding.

Cavaletto insinuates that should prisoners be counted at home, his district, which already benefits from “extra representation”, will lose out on valuable federal and state funds. As Pupovac writes, “He fears that any changes in population could negatively affect the already struggling, rural communities he represents.”

The bill, however, does not apply to federal or state funding.

Ford, the Chicago Rep. who sponsored the legislation, said:

Contrary to popular perception, most inmates serve short sentences, and [when they return home], many of them struggle to find the resources they need to avoid going back to prison.

So why does Cavaletto think that his struggling, rural white constituents deserve representation on the back of Ford’s struggling, urban, and largely black constituents?

“Members of communities I represent put themselves in harm’s way every day guarding Illinois’ most dangerous criminals,” says Cavaletto.

Because electoral districts are based on population, people in prison serve as essentially inert ballast in the redistricting process.

It’s clear to me that while Cavaletto is fighting to have these “dangerous criminals” bussed to his district, he only wants prisoners for their sheer numbers, not as constituents. As Pam Karlan wrote,

because electoral districts are based on population, people in prison serve as essentially inert ballast in the redistricting process.