*Our new chart details how to quantify the progress made across the country.

by Andrea Fenster,

October 26, 2021

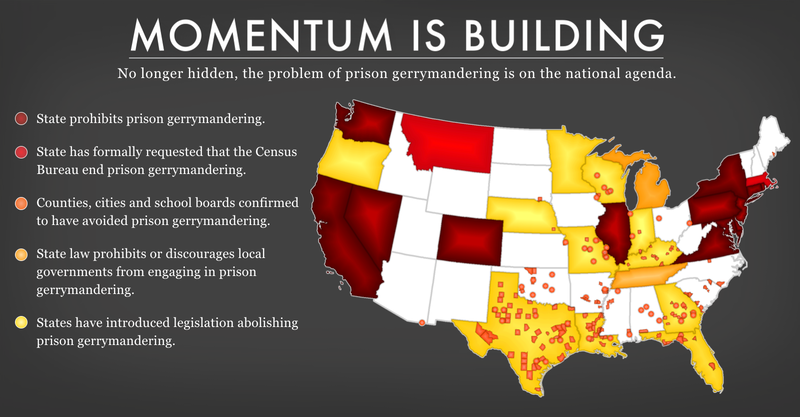

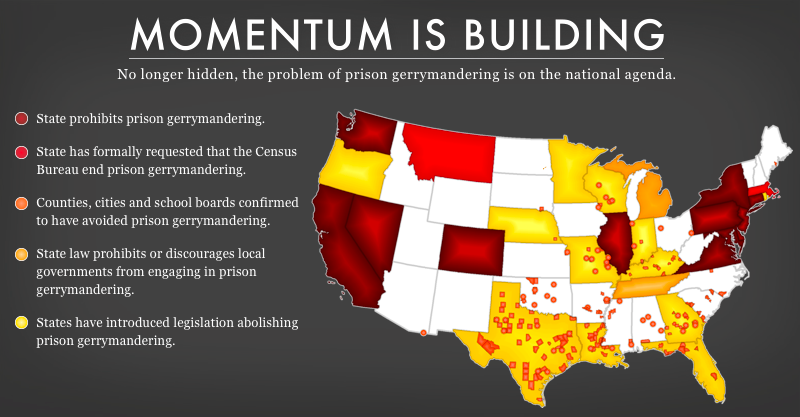

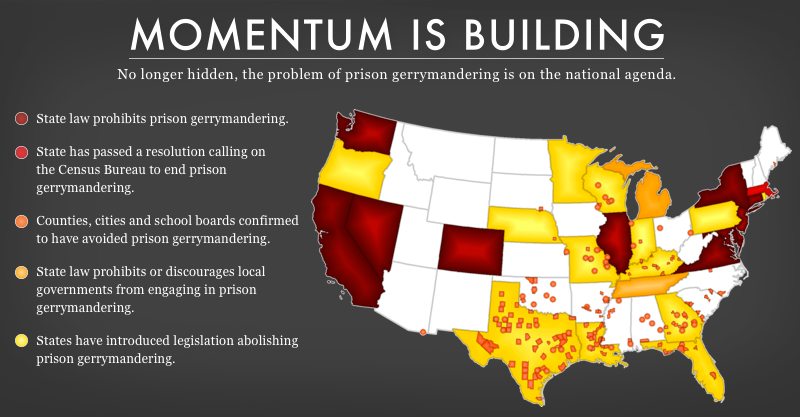

About a dozen states have ended prison gerrymandering. However, the precise number depends on the details. Prison gerrymandering can occur at different levels of government, be solved by different bodies of government, and be eliminated or mitigated through different methods, which can make it somewhat confusing to measure where prison gerrymandering has ended. We have compiled this overview to the progress being made to eliminate prison gerrymandering across the country.

While many people are familiar with redistricting at the Congressional level, these districts are often so big that prison populations rarely affect them. For that reason, Congressional redistricting is not discussed here.

How many states have taken action against prison gerrymandering? 16 states.

California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Illinois, Maryland, Massachusetts, Montana, Michigan, Nevada, New Jersey, New York, Tennessee, Virginia, and Washington have all taken some action to reject prison gerrymandering.

However, these states have taken a variety of actions that affect redistricting in different ways. These differences are important, as they paint a picture of the road still ahead. No matter how you look at it, though, as of today, 47% of the country lives in a state that has formally rejected prison gerrymandering, adding to the growing body of evidence that it is time for the Census Bureau to count people at home.

| State |

State-level legislation effective for 2010 |

State-level legislation effective for 2020 |

State-level legislation effective for 2030 |

State-level non- legislative solutions for 2020 |

Expected state-level non-legislative solutions for 2020 |

State legislation that applies to local governments only |

| New York |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|

| Maryland |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|

| Delaware |

|

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|

| California |

|

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|

| Colorado |

|

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|

| Connecticut |

|

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|

| Nevada |

|

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|

| New Jersey |

|

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|

| Virginia |

|

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|

| Washington |

|

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|

| Illinois |

|

|

✓ |

|

|

|

| Pennsylvania |

|

|

|

✓ |

|

|

| Montana |

|

|

|

* |

✓ |

|

| Massachusetts |

|

|

|

* |

✓ |

|

| Michigan |

|

|

|

|

|

✓ |

| Tennessee |

|

|

|

|

|

✓ |

How many states have taken any action to avoid prison gerrymandering in state-level redistricting? 14 states.

This count includes the 11 states below who passed legislation to formally end prison gerrymandering at the state level, as well as states that have taken other actions to avoid, but perhaps not permanently end, prison gerrymandering.

For example, Pennsylvania did not enact legislation, but the redistricting committee acted on its own to count people at home rather than at the prison where they are incarcerated. It was the first state to address prison gerrymandering through its redistricting committee.

Similarly, Montana is poised to take action against prison gerrymandering. There, members of the redistricting commission recently voted unanimously to take steps toward ending prison gerrymandering in legislative redistricting. They also are asking the state’s governor and congressional delegation to take action to help end the practice and are urging the U.S. Census Bureau to end prison gerrymandering nationwide.

Massachusetts is also included here, even though it does not count people at home. The Massachusetts Redistricting Committee concluded that the state constitution prohibits that solution, instead, Massachusetts is poised to minimize the impact of prison gerrymandering as they did in 2010: by taking prison populations into account when redistricting to ensure that they will not be concentrated in a small number of districts. Massachusetts also passed a joint resolution in 2010 calling on the Census Bureau to provide data that counts incarcerated people at their residence, not the prison. Our analysis of the proposed draft maps shows even further progress in avoiding prison gerrymandering for the 2020 districts.

How many states have enacted legislation addressing prison gerrymandering at any level? 13 states.

In addition to the 11 states that have ended prison gerrymandering through legislation at the state level, there are 2 states that have enacted state-level legislation that applies only to local governments.

Michigan’s laws require counties, cities, and towns to exclude people in state prisons who are not residents of the city or county for election purposes. Tennessee, on the other hand, explicitly allows counties to exclude people in correctional institutions who cannot register in the county as voters, but does not require it.

How many states have solved prison gerrymandering during state-level redistricting? 12 states.

Here, Illinois and Pennsylvania are included, but not Massachusetts or Montana. While Massachusetts may avoid or mitigate prison gerrymandering by taking prison populations into consideration, it does not directly solve the problem. Regardless, neither Massachusetts nor Montana is included here because the redistricting processes in those states are still ongoing.

How many states have passed legislation ending prison gerrymandering at the state level? 11 states.

This includes all states that have passed or enacted legislation to end prison gerrymandering, and where that language is mandatory, meaning that redistricting must exclude prison populations or count them at home. These 11 states are California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Illinois, Maryland, Nevada, New Jersey, New York, Virginia, and Washington. All of these states are included in the above categories.

How many states will not prison gerrymander in their state districts in the 2020 redistricting cycle? 11 states, so far.

Eleven states will not use prison populations to pad political districts this cycle. Pennsylvania is included here because its redistricting committee acted on its own to count people at home for the 2020 redistricting cycle. However, Illinois is excluded because that legislation is not effective until 2025, in time for the 2030 redistricting cycle. Neither Massachusetts nor Montana are included here; while we expect both states to avoid prison gerrymandering, neither has formally finalized their plans yet.

So, how many states have ended prison gerrymandering? The answer is somewhere between 11 and 16 states, depending on how complete and futureproof their solutions are. On top of that, more than 200 impacted local governments, including counties, cities, towns, and school boards, have also acted to end prison gerrymandering. By comparison, in the 2010 cycle, only 4 states—New York, Maryland, Delaware, and California—had passed legislation and only 2—New York and Maryland—had implemented it. But as long as the Census Bureau continues to count incarcerated people in the wrong place, any state-based solution is a stop-gap measure. While the different approaches that states have taken may be important to know about, these differences should not obfuscate the larger trend towards ending prison gerrymandering.

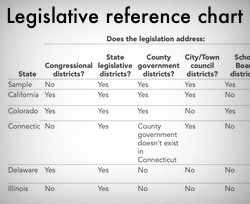

For detailed information on the different types of solutions to prison gerrymandering, please see our solutions page and our legislation quick-reference chart.