National Conference of State Legislatures report outlines experiences and recommendations from states that implemented reforms in the 2020 redistricting cycle.

by Aleks Kajstura,

May 2, 2023

In a new report from the National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL), state governments have a clear message for the Census Bureau: You created prison gerrymandering, you need to fix it.

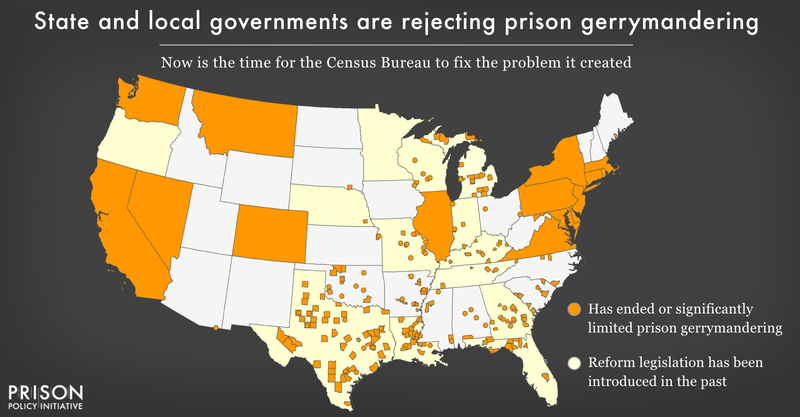

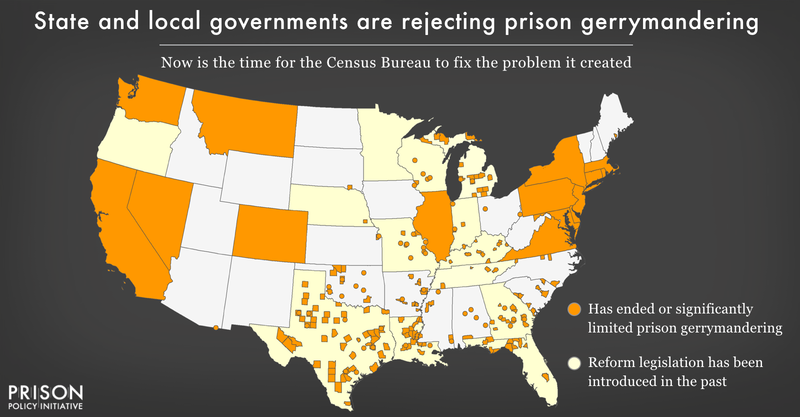

The report examines state implementation of prison gerrymandering reforms after the 2020 census. Prison gerrymandering is a problem created by the Census Bureau’s policy of counting incarcerated people as residents of prison cells rather than their home communities. When states use those Census counts to draw legislative districts, they unintentionally distort political representation by unfairly giving people who live closest to prisons a louder voice in government, to the detriment of everyone else. To fix this problem, more than a dozen states had to adjust Census redistricting data to count incarcerated people at home after the 2020 census.

Based on interviews of redistricting officials in the 13 states that addressed prison gerrymandering when drawing new state legislative lines after the 2020 census, the report gives insights into the challenges they faced in implementing these reforms and offers recommendations to overcome those obstacles. The report makes clear that state officials recognize this problem is important, worth fixing, and the Bureau should do the fixing.

This report is well-timed. Last week Rep. Deborah Ross of North Carolina, along with Rep. Mark Pocan of Wisconsin, Rep. Emanuel Cleaver of Missouri, and Rep. Emilia Strong Sykes of Ohio, introduced a bill in Congress to end prison gerrymandering nationwide and Montana joined the growing list of states that have permanently addressed this problem. With roughly half of U.S. residents now living in a city, county, or state that has taken action to end prison gerrymandering, the emerging consensus on this issue is clear.

Everyone agrees — Census Bureau shouldn’t leave this work to the states

No recommendation looms larger in the report than the first one, which calls for the Census Bureau to take on the task of reallocating incarcerated people back to their home communities, either automatically or at the request of states. This is a roundabout way of saying what we’ve long maintained: the most efficient and effective way to solve this problem is for the Census Bureau to change its policy to count incarcerated people at their true homes.

The Census Bureau is legally required to provide data that is fit for use by states for redistricting purposes. However, the broad agreement on this issue suggests the agency is not meeting this critical obligation.

On the biggest challenges, states’ hands are tied

As the report details the challenges states faced implementing prison gerrymandering reforms, a theme quickly emerges: The biggest challenges are ones the Census Bureau created or is the agency best positioned to solve.

1. Census and other federal agencies impede state efforts

The report shows that the Bureau not only forces states to do the heavy lifting of counting incarcerated people in their home district, it and other federal agencies often inject additional speedbumps into the process.

For example, the Census Bureau frequently failed to accurately count correctional facilities, counting many facilities in the wrong place, and it failed to count some altogether. The Bureau’s bumbling in this regard was so bad this decade that it created a dedicated operation to allow governments to review its work. While these errors were particularly egregious and numerous in the pandemic-era, 2020 Census, they exist to some extent in all decades. These issues, while theoretically surmountable, add unnecessary burden to states trying to create useful redistricting data out of the Census tabulations under a tight timeline.

Additionally, many states expressed frustration with the Bureau’s lackluster geocoding tools, which are supposed to help them perform this reallocation. According to the report, the Bureau’s tool was the only one that elicited staff concerns, noting, “of the seven states that told NCSL they attempted to use the bureau’s geocoder, only one reported no issues with its user interface or concerns with its accuracy.”

The Census Bureau wasn’t the only federal agency to make states’ jobs harder. The Bureau of Prions (BOP) refused to cooperate with states, denying their requests to share address information for their residents. The report notes, “Nine of the 13 states’ reallocation policies encompassed people incarcerated at federal prisons, yet none of those states was able to receive inmate data from the Bureau of Prisons. All nine states requested data multiple times through official and unofficial channels to no avail.” The Bureau of Prisons controls the address information for about 150,000 incarcerated people nationwide.

It is important to note that the Census Bureau is the only agency able to overcome BOP stonewalling. How? By counting incarcerated people in their home communities in the first place.

2. Extra steps and unnecessary delays

Redistricting deadlines are already tight. The report shows the Census Bureau makes them even tighter by forcing states to spend precious time adjusting data to address prison gerrymandering. States recognize this is important, which is why even the state with the shortest redistricting deadline, New Jersey, which has only 30 days after the Census publishes its data to complete its redistricting, considered it worthwhile to take the time to adjust the Census data to count people at home. And even states like Montana, which made the decision to address prison gerrymandering later, ended up with redistricting data that better reflected their residents and thus was more suitable for redistricting than what the state received from the Census Bureau.

However, time is a limited resource for states; when states have to fix Census data, they have less time to focus on their primary task of drawing legislative districts. If the Bureau counted incarcerated people at home, it wouldn’t force states to choose between redoing the Census’s work and devoting more time to actual redistricting.

During this redistricting cycle, the COVID-19 pandemic caused significant delays and added uncertainty to the process. Most notably, the Census Bureau delayed data publication, further squeezing these already tight timelines. While the pandemic is unlikely to be an issue in future redistricting cycles, this experience shows why, in an unpredictable process, when time is at a premium, the Bureau should not increase the workload of the states.

While states can mitigate delays by passing legislation early in the decade to allow for data collection and planning before redistricting is looming, none of that effort should be necessary — the Census Bureau is unfairly shifting the burden of counting incarcerated people at home to the states.

3. Data quality issues magnified for states

The Census Bureau has one huge advantage that states don’t during redistricting: it has decades of experience working with this data and a full decade to prepare and troubleshoot problems it encounters; meanwhile, states are usually working on a short timeframe, measured in weeks and months.

This means the Census Bureau has usually seen and solved many of the problems states most frequently encounter, even before the data is collected. However, instead of solving these problems once, and passing that solution on to the states, it forces each state to muddle through them and develop their own process for solving them.

For example, one frequent problem states encountered was that their Departments of Corrections (DOCs) often collected and recorded race and ethnicity data differently than the Census Bureau. This is not a problem unique to DOCs and the issue of prison gerrymandering, so the Bureau has encountered it before and has a way of addressing it. However, instead of providing that solution to the states, each state had to navigate this problem on its own, expending valuable time and resources.

Similarly, states took different approaches to handling unknown or unmappable addresses. In some states, this was driven by legislative language, but in others, the task of making the decision fell to the staff.

And there were some problems states were just unable to solve, no matter how hard they tried. For example, each state only had the address data for people it incarcerated. That means states could not count their residents who were incarcerated in other states. This kind of arbitrary jurisdictional roadblock would not be an issue for the Census Bureau.

Some of these issues could be solved with additional years of address gathering (on intake at the correctional facilities), and many of the staff’s concerns about vague legislative guidance can be solved by bringing some of the language from our model legislation into the state’s law.

But in the end, the Census Bureau is better situated to count incarcerated people at home. So why is it forcing states to jump through so many hoops?

Census Bureau needs to solve the problem it created

The sheer number of states that ended prison gerrymandering was one of the most significant positive developments of the 2020 redistricting cycle. But it wasn’t without its challenges. Unlike many redistricting challenges that states face, though, prison gerrymandering was not self-inflicted and instead was created by outdated Census Bureau policies. The Census Bureau must start being more responsive to state redistricting needs.

The number of states addressing this problem will almost certainly grow by 2030. This NCSL report is powerful evidence that it is time for the Census Bureau to listen to the states and finally count incarcerated people at home.