The Bureau is aware of our organizations' concerns about prison gerrymandering, but side-stepped our request to prioritize developing a solution.

by Peter Wagner,

May 17, 2013

Acting Director explains Bureau’s immediate priorities but sidesteps request to prioritize developing a solution to prison gerrymandering

The Census Bureau has replied to the February 14 letter from 210 organizations urging it to make “developing a methodology to tabulate incarcerated people at their home addresses a near-term priority.” I wanted to share the Census Bureau’s response, along with some of my thoughts about it. In a nutshell, the Bureau is aware of our organizations’ concerns about prison gerrymandering, but side-stepped our request to prioritize developing a solution.

Our coalition letter was intended to inform the Census Bureau that a diverse group of stakeholders wants the agency to start planning how to tabulate incarcerated people at home. In our view, the Bureau needs to recognize that the prison count is the largest and most visible failing with regard to where it tabulates people in the decennial enumeration, and start researching solutions now.

But in his reply to our letter, Acting Director Thomas Mesenbourg explained that the Bureau would not focus, in the near term, specifically on the issue of where the census tabulates incarcerated people. Instead, Mr. Mesenbourg described how researching solutions to prison gerrymandering fits into the Bureau’s current longer-term agenda: as one part of a much broader inquiry on residence rules that will take place — budget permitting — in Fiscal Year 2015. That falls far short of what we asked for, but the clarity of the Bureau’s response is helpful in determining our next steps. I wanted to share some further thoughts about the Acting Director’s letter, and some ideas moving forward.

The Bureau’s immediate priorities

The reply letter nicely summarizes the overall challenges the Bureau faces to maintain the quality of the decennial census while controlling costs, listing the four areas where the Bureau is currently focusing its energy. The Bureau then gives an update on an important moving target: exactly when research on improving the group quarters count could take place.

The problem of prison gerrymandering may be one of the most glaring defects in the Census, but, as the reply letter explains, the Bureau is instead prioritizing work on fundamental changes in the structure and operations of the decennial census in order to trim several billion dollars from the cost. I can see how the Census Bureau might, in contrast, view improving the tabulation of just one group of people — no matter how glaring the problem — as a lower priority.

The strategic challenge for our movement is not the complexity of the research required, it is the timing. Improving how incarcerated people are counted is not rocket science, but it does requires diligent planning. After all, people in prisons and jails are the only population in the country that the government counts multiple times every day. The Bureau needs sufficient time to find solutions to legitimate questions about the best way to collect and process these data.

In the reply letter, the Acting Director says that “research [on] other aspects” of the 2020 Census can begin only after the “high-level design” is completed, in 2015. This delay is potentially, though not definitively, problematic for the efforts to end prison gerrymandering by the next redistricting cycle. 2015 isn’t necessarily too late to begin researching how to tabulate incarcerated people at home in 2020, but it leaves a very small window of opportunity because the details of the 2020 Census will be locked in place long before 2020 rolls around. Unless the Bureau articulates a clear intent to pursue methods to tabulate incarcerated people at their homes of record, the passage of time will leave the Bureau will no choice but to continue its outdated methodology in the 2020 Census.

No clear statement on research priorities

While our letter acknowledged the Bureau’s budgetary challenges, our letter asked the Bureau to include ending prison gerrymandering in its near-term priorities. Unfortunately, the reply did not address the matter of priorities directly or explain why the Bureau can’t begin the process of planning improved ways to tabulate incarcerated people while it completes redesigning other components of the Census. Supporters of the constitutional principle of “One Person, One Vote” should be very concerned by the prospect of relegating the question of how incarcerated people are counted — the most visible fairness flaw in the decennial census — to only one piece of a larger research question that will not start until 2015, budget permitting.

The Role of Congress and the Bureau’s fear of controversy

The Census Bureau has the power to end prison gerrymandering, and the letter’s summary of the Bureau’s residence rules methodology since the Census Act of 1790 supports our position that the Bureau has the authority to revise its methodology to keep pace with social and demographic change. The question of where to tabulate incarcerated people is clearly within the Bureau’s discretion, but, as the Acting Director noted, the Bureau looks to Congress before making any changes that could be vulnerable to criticism.

Unfortunately, this fear of political controversy may be leading the Census Bureau to prioritize the consequences of changing the residence rule over the consequences of the status quo for the health of our democracy. The Acting Director’s one nod to the rule’s larger implications for democracy is that “[w]e understand fully the major impact on different states as well as counties and municipalities … [during] redistricting if we considered changing the residence rule” (emphasis added). Ironically, the Bureau’s own commissioned experts at the National Research Council of The National Academies had no such problem acknowledging the need for change, noting the current rule’s detrimental impact on democracy. During last decade’s review of the residence rules, the expert panel concluded that “[t]he evidence of political inequities in redistricting that can arise due to the counting of prisoners at the prison location is compelling.”

Even as the Acting Director’s reply letter stating that the Bureau “must inform and try to ascertain the will of the Congress on such a major change” was in the mail to me, the Census Bureau received evidence of congressional concern about the Bureau’s current policy. On April 1, 2013, 18 members of Congress wrote to the Bureau about why properly tabulating incarcerated people is important to state and local governments. They wrote, “We… urge the Census Bureau to take the steps necessary to ensure that Census 2020 counts prisoners at their home addresses to assist state and local governments in accurately representing these populations.”

Finally, the Bureau’s concern that “major change … regarding apportionment” necessitates the assent of Congress is a red herring. Congressional apportionment is unlikely to be affected by tabulating incarcerated people at home because most people do not cross state lines when they are incarcerated.

Moving forward

But beyond congressional weigh-in, the Census Bureau wants to get the input of as many stakeholders as possible before making a change to where incarcerated populations are counted. That is yet another reason why the comparatively straightforward activity of improving where incarcerated people are tabulated needs to start sooner rather than later.

Finally, the Bureau’s reply is a good indication of how much work we have left to do to establish why it is necessary to change where incarcerated people are tabulated. The letter, in my view, both understates the impact of prison gerrymandering on local and state governments and undervalues the Bureau’s own significant efforts to help those local governments by producing the Advance Group Quarters Summary File. This file, which the Bureau produced for the first time ever in 2010, was incredibly helpful to many state and local governments that wanted to eliminate, minimize or at least consider avoiding the effects of prison gerrymandering.

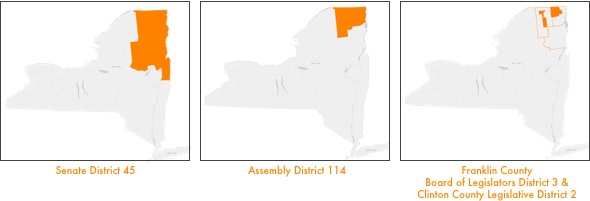

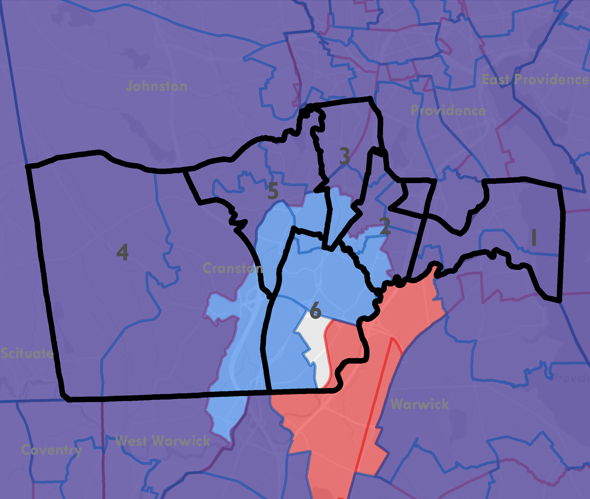

The driving reason to address prison gerrymandering is its dramatic impact on state and local governments. It is easy to understand why the Census Bureau, as a federal agency, might prioritize questions of congressional apportionment over state legislative, and even county/municipal, redistricting. But congressional apportionment is not the primary concern because prison populations are rarely significant in determining a 700,000 person Congressional district. The real impact of prison gerrymandering is at the state legislative level and, especially, at the county/municipal level. The smaller the legislative district, the more likely it is that a single prison could make up a large part, or even an actual majority, of the district. Taken together, prison gerrymandering’s impact is pervasive, and the overwhelming majority of the nation will benefit in at least one way when the practice comes to an end. As general messaging point, our movement needs to ensure that the real reasons to end prison gerrymandering remain in focus.

Moving forward, it is imperative that the Census Bureau continue to hear from all of its stakeholders — at the federal, state and local levels — that now is the time to address the problem of prison gerrymandering in order to resolve the problem by 2020. We shouldn’t have to wait until 2030 to fix such an obvious flaw in the Census Bureau’s methodology that compromises state and local democracy around the nation.