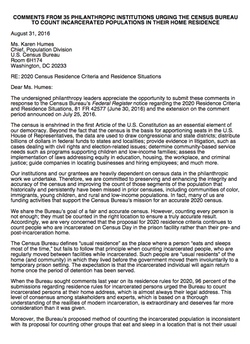

35 foundation leaders join the call for new residence rules for incarcerated people

35 foundation leaders urge the Census Bureau to count incarcerated people at home for a fair and accurate 2020 Census.

by Alison Walsh, September 2, 2016

The Census Bureau has heard from a range of voices on the issue of where to count incarcerated people for the 2020 Census. Last year, a chorus of civil rights and voting rights organizations, legislators, law professors, and formerly incarcerated individuals all asked the Bureau to update its methodology and start counting incarcerated at their home addresses. Despite this consensus, the Bureau announced plans last June to continue counting incarcerated people as “residents” of prison facilities.

On Wednesday, 35 foundation leaders – representing organizations such as the Ford Foundation, Annie E. Casey Foundation, and Bauman Foundation – joined together and also urged the Census Bureau to end the prison miscount. They explain the importance of an accurate census count both in their work and for communities they serve:

Our institutions and our grantees are heavily dependent on census data in the philanthropic work we undertake. Therefore, we are committed to preserving and enhancing the integrity and accuracy of the census and improving the count of those segments of the population that historically and persistently have been missed in prior censuses, including communities of color, immigrants, young children, and rural and low-income populations. In fact, many of us are funding activities that support the Census Bureau’s mission for an accurate 2020 census. […]

[C]ounting every person is not enough; they must be counted in the right location to ensure a truly accurate result.

The coalition finds two key problems with the Census Bureau’s proposal: it overlooks the true meaning of a “usual residence” and goes against public input.

The Census Bureau seeks to count everyone at his or her “usual residence,” defined as the place where a person “eats and sleeps most of the time.” Following this guideline should lead the Bureau to count incarcerated people at their home communities. “Such people are ‘usual residents’ of the home (and community) in which they lived before the government moved them involuntarily to a temporary prison setting.” Incarceration, the authors point out, “is a temporary stay.” People in correctional facilities “have a usual home elsewhere to which they will eventually return once the sentence is served.”

Furthermore, the foundation leaders note that the Census Bureau’s proposal ignores the overwhelming call for change.

When the Bureau sought comments last year on its residence rules for 2020, 96 percent of the submissions regarding residence rules for incarcerated persons urged the Bureau to count incarcerated persons at their home address, which is almost always their legal address. This level of consensus among stakeholders and experts, which is based on a thorough understanding of the realities of modern incarceration, is extraordinary and deserves far more consideration than it was given.

In the past, the Census Bureau has demonstrated a willingness to change its policies in response to unique living situations. “Those changes, however, have not extended to counting incarcerated people in the right place.” For example, the Bureau decided to count military personnel deployed overseas at their home addresses in 2020, “even though there were far fewer comments related to this subject than on the prison miscount.”

Still, it is not too late for the Bureau to lay the groundwork for an accurate 2020 Census by finally deciding to count incarcerated people at home. The coalition concludes: “We hope the Bureau’s final 2020 Census Residence Criteria reflects this change for the 2020 Census.”