Federal judge’s ruling clears the way for Louisiana to end prison gerrymandering without waiting until 2030

U.S. District Judge Shelly Dick said current maps deprive Black residents of political representation.

by Mike Wessler, March 27, 2024

Last month, U.S. District Judge Shelly Dick struck down Louisiana’s state legislative districts, noting that they unfairly deprived Black residents of political representation in violation of the Voting Rights Act. She ordered the state to draw new legislative maps to resolve this issue.

Importantly, in her ruling, Judge Dick noted how the over-incarceration of Black people harms their ability to engage with their government, saying:

“The preponderance of the evidence proved that Black voters’ participation in the political process is impaired by historic and continuing socio-economic disparities in education, employment, housing, health and criminal justice.”

While the judge did not specifically cite prison gerrymandering in her ruling, it is an issue that makes the inequalities at the heart of the case even worse. Prison gerrymandering is a problem created because the Census Bureau counts incarcerated people as residents of the wrong place — a prison cell — rather than their actual homes. When state governments then use the Bureau’s data to draw new legislative maps during their redistricting process, they inadvertently give residents who live closest to prisons greater political clout at the expense of everyone else.

When the Louisiana legislature convenes to draw new legislative districts to comply with the Judge’s order, its maps should address the injustice of prison gerrymandering.

Prison gerrymandering diminishes Black political representation in Louisiana

Louisiana is the incarceration capital of the world, locking up not only a greater share of its residents than any other state in the country but also more than any nation on the planet. So it should come as no surprise that prison gerrymandering has stark consequences in the state.

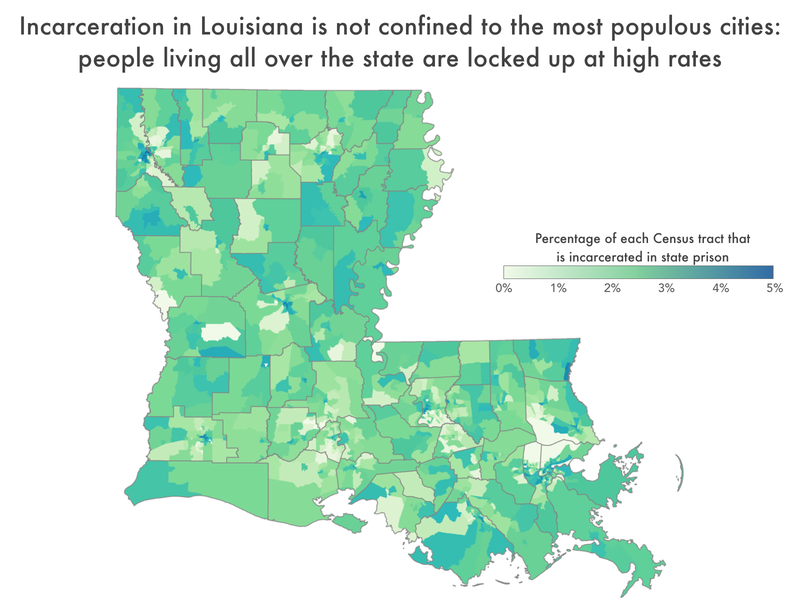

A unique dataset, which we gathered with the help of Louisiana-based Voice of the Experienced and Redistricting Data Hub, gives us a more precise look at how this plays out.1 Most importantly, we can see that incarcerated people come from all over the state. This matters because under the current flawed way the Census Bureau treats incarcerated people, the 26,000+ people in state custody are counted in just a handful of state prisons, dramatically inflating the population of those communities — and, with it, their political clout.

This data shows that prison gerrymandering robs nearly every state legislative district and its residents of some of their political voice. This political clout is then given to those districts that contain prisons.

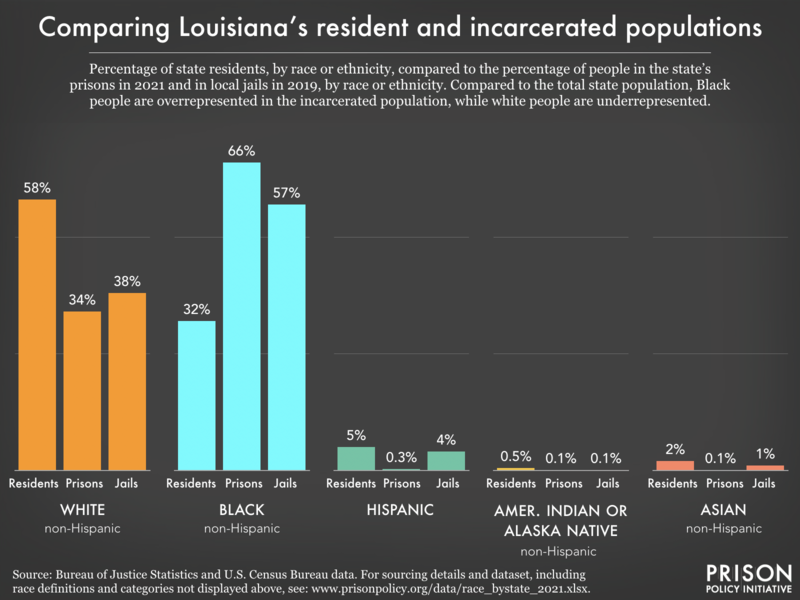

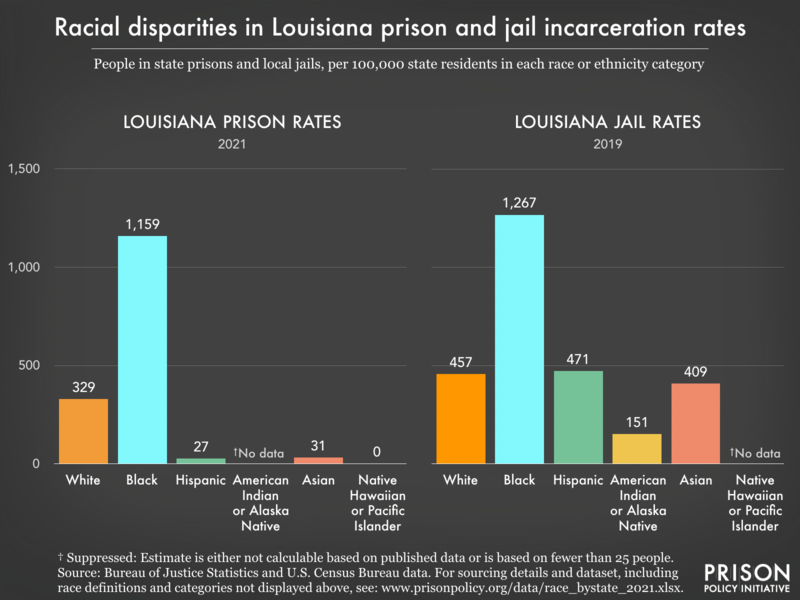

While nearly every community is harmed by prison gerrymandering, that pain is not felt equally. Louisiana has stark racial disparities in its prisons. Black residents account for 32% of the state’s population, but they account for 66% of the people in state prisons.

With such dramatic disparities in incarceration in the state, it is clear that prison gerrymandering is undermining Black political representation in Louisiana.

Prison gerrymandering gives two majority-white districts a particularly loud voice in government

Because of prison gerrymandering, people in Louisiana who happen to live close to state prisons get more political clout at the expense of every other resident of the state.

In Louisiana, two majority-white districts particularly benefit from this dynamic. First is House District 22, which contains a federal prison in Pollock. The other is House District 18, home to the Louisiana State Penitentiary, better known as Angola Prison.

In each of these places, incarcerated people make up more than 11% of the district population. As a result, 89 actual residents of these districts have the same political clout as 100 residents of any district in the state without a prison.

| Percentage of the district population that is incarcerated | Percentage of the district population that is white (non-Hispanic) | |

|---|---|---|

| House District 22 | 11.73% | 62% |

| House District 18 | 11.36% | 62% |

Addressing prison gerrymandering will correct this imbalance and ensure that residents of these districts get the same voice in government — no more and no less — as every other resident of the state.

Louisiana’s embrace of failed, punitive criminal legal system policies shows why prison gerrymandering matters

At its core, the failure of Louisiana to address prison gerrymandering is an issue of political representation. However, this isn’t simply an academic exercise about ensuring everyone has an equal voice. It has real and dramatic consequences. To see this, you have to look no further than the recently ended special session of the Louisiana legislature.

The state’s new governor called the special session under the guise of focusing on crime despite the evidence that crime is at its lowest levels in roughly 60 years. During the session, lawmakers passed a slew of regressive policies that will increase prison populations and make the criminal legal system more punitive, including effectively eliminating parole, trying more young people as adults, and expanding the use of the death penalty.

It is reasonable to conclude that lawmakers who benefit politically from prison gerrymandering and the state’s large prison population have a strong incentive to protect and even grow this advantage by supporting the type of punitive criminal legal system policies passed during the special session. On the other hand, lawmakers who represent districts that have large numbers of residents in state prisons are more likely to seek solutions to the root causes of incarceration, such as poverty and untreated mental health and substance use issues. This conclusion was borne out during the special session when the two lawmakers who represent House Districts 22 and 18 — and benefit most from prison gerrymandering — supported all of the new draconian changes to the criminal legal system.

Addressing prison gerrymandering will help to disrupt this incentive toward bad policy and ensure every resident gets an equal say in government.

Now is the time for Louisiana to end prison gerrymandering

Eighteen states — including “red” states like Montana, “blue” states like New York, and “purple” states like Maine — have recognized the injustice of prison gerrymandering and rejected the flawed Census data. Instead, they took it upon themselves to correct the redistricting data to provide more equal representation to their residents. Progress on this issue has been so swift that the staunchly bipartisan National Conference of State Legislatures recently called the movement to end prison gerrymandering “the fastest-growing trend in redistricting.”

Louisiana should join this rapidly growing list.

We don’t yet know when the legislature will take action in response to the court ruling, and the judge did not set a clear timeframe for when they must act. However, when they do, their maps should address the problem of prison gerrymandering. Failure to act would mean that residents of the state — particularly Black residents — will continue to have their political representation diminished until at least 2031.

Footnotes

-

This analysis only includes data on the people incarcerated in state prisons in Louisiana. It does not include information on people held at the two federal prisons in the state. ↩