Minnesota ends prison gerrymandering

With Governor Tim Walz's signature, the state is the latest to reject the Census Bureau’s flawed and outdated way of counting incarcerated people.

May 20, 2024

On Friday, Minnesota Governor Tim Walz signed HF 4772 — an omnibus elections policy bill — into law, officially ending prison gerrymandering in the state. With this action, Minnesota joins the rapidly growing list of states that have taken action on this issue. The measure requires state and local governments to count incarcerated people at their home addresses when drawing new political districts during their redistricting process.

Prison gerrymandering is a problem created because the Census Bureau incorrectly counts incarcerated people as residents of their prison cells rather than their home communities. As a result, when states use Census data to draw new state or local districts, they inadvertently give residents of districts with prisons greater political clout than all other state residents.

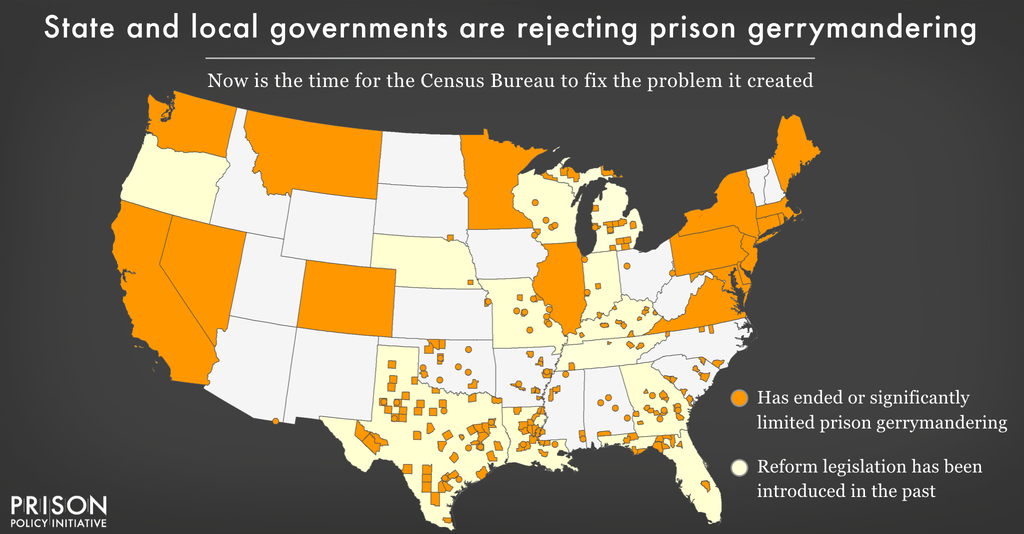

“With this law, yet another state has rejected the Census Bureau’s flawed way of counting incarcerated people to ensure its residents have an equal voice in their government,” said Aleks Kajstura, Legal Director of the Prison Policy Initiative and the head of the organization’s campaign to end prison gerrymandering. “Roughly half the country now lives in a place that has ended prison gerrymandering. With so many places taking action on this issue, it raises the question, ‘Will the Census Bureau listen to the growing consensus on this issue, or will it cling to its outdated and misguided way of counting people in prisons and jails in 2030?'”

The provisions ending prison gerrymandering in the state were initially introduced as standalone measures and were rolled into this omnibus election bill.

Most states have clauses in their constitutions or statutes that explicitly say that prisons are not a residence — whether someone is incarcerated away from home for a few months or a few decades — yet the Census Bureau continues to count people as if they are. The Census Bureau has the authority to change how it counts incarcerated people and officially end prison gerrymandering at the national level, but inaction has forced state and local officials to pass reforms and shoulder the burden of correcting flawed Census redistricting data to count incarcerated people at home.

In addition to Minnesota, eighteen other states — including “red” states like Montana, “blue” states like New York, and “purple” states like Maine — have recognized the impact of prison gerrymandering on political representation and have taken action to provide more equal representation to their residents. Progress on this issue has been so swift that the staunchly bipartisan National Conference of State Legislatures recently called the movement to end prison gerrymandering “the fastest-growing trend in redistricting.”

With Minnesota adding itself to this rapidly growing trend, there is yet another reason for the Census Bureau to finally change how it counts incarcerated people and end prison gerrymandering nationwide.