With unanimous, bipartisan support, Montana ends prison gerrymandering

State asks Census Bureau to end this problem nationwide.

February 13, 2023

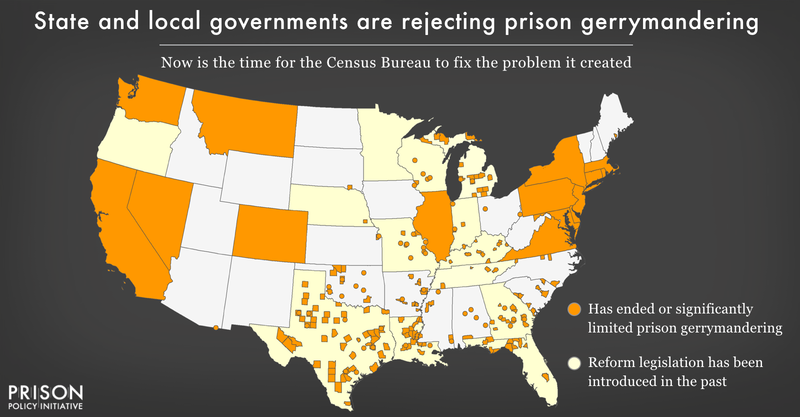

For immediate release — This weekend, Montana’s Districting and Apportionment Commission officially approved new legislative maps that count incarcerated people at their homes instead of in prison cells, ending prison gerrymandering in the state. During the redistricting process, ending prison gerrymandering consistently received unanimous, bipartisan support from commission members and was championed by Native American leaders in the state. Montana is the third state to address this problem without legislation1. It is among more than a dozen states and over 200 local governments that have ended the practice.

Prison gerrymandering is a problem created because the Census Bureau incorrectly counts incarcerated people as residents of their prison cells rather than their home communities. As a result, when states use Census data to draw new legislative districts, they inadvertently give residents of districts with prisons greater political clout than all other state residents. Montana’s actions limited that injustice in the state.

“The maps approved by Montana’s redistricting commission will ensure that all residents of the state have an equal voice in the decisions made by their legislative leaders,” said Aleks Kajstura, Legal Director of the Prison Policy Initiative and a long-time advocate for reform. “This victory represents a clear, bipartisan rebuke of the broken and outdated way the Census Bureau counts incarcerated people.”

In addition to approving new legislative districts, the Commission has called on the Census Bureau to count incarcerated people at home in 2030. In a letter to the Bureau, it notes this change “would create more complete, useful redistricting data for policymakers and line drawers in the future.”

Montana’s success was not without difficulties. As a result of the Census Bureau’s flawed method of counting incarcerated people, the Commission was forced to hire outside experts to fix the data at taxpayer expense. Even still, the state was still hampered by missing address data for many incarcerated people.

“The members of the Districting and Apportionment Commission should be commended for addressing this problem under a tight timeline and with considerable obstacles,” Kajstura said. “The Census Bureau should act on the Commission’s request to change how it counts incarcerated people as it develops rules for the 2030 Census.”

Roughly half of U.S. residents now live in a city, county, or state that has taken action to end prison gerrymandering.

Commission members also asked the state’s Congressional delegation to pass legislation to end prison gerrymandering, asked the state’s governor and Department of Corrections to collect home addresses for incarcerated people, and brought forward legislation to permanently address this issue in the state. The legislation has already passed the Senate with bipartisan support and is currently making its way through the House.

The national movement to end prison gerrymandering began in 2001 when the founders of the Prison Policy Initiative discovered that the sheer size of the prison population, combined with an outdated Census Bureau rule to distort political representation in this country. Since then, more than a dozen states and over 200 local governments have taken action to address this problem.

Footnotes

-

Pennsylvania and Rhode Island also addressed prison gerrymandering through their redistricting commissions. ↩