Connecticut Gov. Ned Lamont signs bill ending prison gerrymandering

Connecticut becomes the 11th state to end the practice of prison gerrymandering.

May 27, 2021

For Immediate Release – Yesterday, Connecticut Governor Ned Lamont signed a bill ensuring that people in state prisons will hereafter be counted as residents of their home addresses when new legislative districts are drawn. The new law makes Connecticut the eleventh state to end the practice known as prison gerrymandering, after Illinois passed its own bill earlier this year.

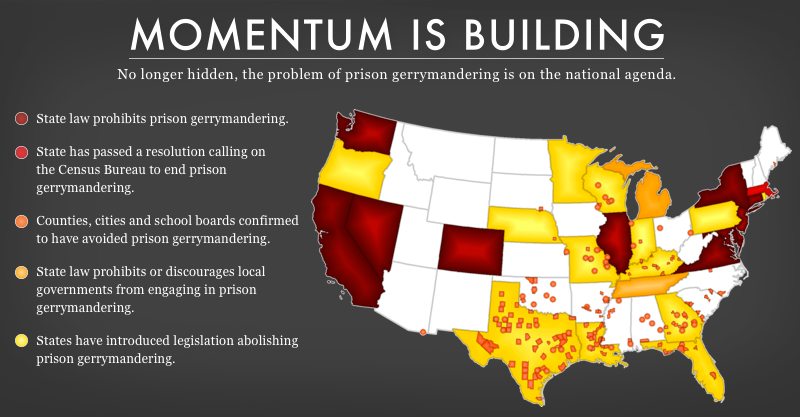

The national movement against prison gerrymandering began in 2001 when the founders of the Prison Policy Initiative discovered that the sheer size of the prison population was combining with an outdated Census Bureau rule to distort political representation in this country. With the victory in Connecticut, over 35% of US residents now live in a state, county, or municipality that has formally rejected prison-based gerrymandering.

Most people in prison come from districts other than those in which they are incarcerated, and return to those home districts after release. Incarcerated people typically have strong attachments to their home communities, but no attachment to the community surrounding the prison. However, the Census Bureau counts all incarcerated people as residents of their prison cells. As a result, when states use Census counts to draw legislative districts, they inappropriately enhance the representation of people living in districts containing prisons.

Prison gerrymandering has a particularly significant impact on communities of color. The majority-white residents of seven state House districts in Connecticut have received significantly more representation in the legislature because each of their districts included at least 1,000 incarcerated African Americans and Latinos from other parts of the state. Eighty-six percent of the state’s prison cells are located in disproportionately white House districts.

“All districts in Connecticut send people to prison, but only some districts contain prisons,” said Aleks Kajstura, Legal Director of the Prison Policy Initiative. “Counting incarcerated people as residents of the prison gives extra political representation to those districts, and dilutes the votes of everyone who does not live next to the prison. This new law will make legislative districts fairer by requiring people in prison be counted as residents of their hometowns.”

In enacting this legislation, the state has now caught up to the redistricting practices of the towns of Enfield and Cheshire, which both have large prisons within their borders and already refused to use the prison populations when drawing their local town districts.

Connecticut’s new law is the result of years-long efforts by Senator Gary Winfield and advocates, including Common Cause Connecticut the NAACP of Connecticut, and the Yale Law Peter Gruber Rule of Law Clinic. The law will go into effect for this year’s redistricting process, bringing an immediate end to the prison-driven distortion of representation in Connecticut.

The upcoming redistricting cycle means the clock is ticking for other states to end prison gerrymandering through legislation this year. But every state can still take action to prevent prison-driven election distortion. Legislation is not the only way to end prison gerrymandering before new districts are drawn: State and local redistricting officials can also minimize the impact of the Census’ prison counts by using the “group quarters” table that will be published with the usual redistricting data. The Census Bureau is publishing the table to make it easier for states to identify correctional facilities in their redistricting data.

Connecticut’s new law applies only to redistricting and unfortunately carves out a small exception for people serving sentences of life without the possibility of parole, who account for roughly 0.5% of the prison population. The legislation will not affect federal or state funding distributions.