Building momentum against prison gerrymandering

Diverse support for ending prison gerrymandering builds momentum for action nationwide.

by Aleks Kajstura, December 18, 2020

Prison gerrymandering can feel like a complex, political quirk. Talking about Census Bureau policy and how the Bureau interprets its own sometimes-arcane “residence rules” can feel like getting deep in the weeds of policy. But prison gerrymandering is not a fringe issue. It has real-world implications for representation and public policies — and there are proven solutions. Since the Prison Policy Initiative and others have been working to solve this problem, we have seen growing public support and reform legislation passed around the country.

The problems stem from the way the Census Bureau conducts its counts. When counting the population every ten years, the Bureau tabulates incarcerated people as if they were residents of the locations where they are confined, even though they remain legal residents of their homes. When the resulting data is then used to draw legislative districts, all of a state’s incarcerated persons are credited to a small number of districts that contain large prisons. This has the effect of enhancing the representation of those districts and diluting representation of everyone else in the state, distorting policy decisions statewide. And since incarcerated populations are disproportionately Black and Latino, minority voting strength is diluted in the process. (Although this affects representation, it fortunately does not have major funding implications, for various reasons.)

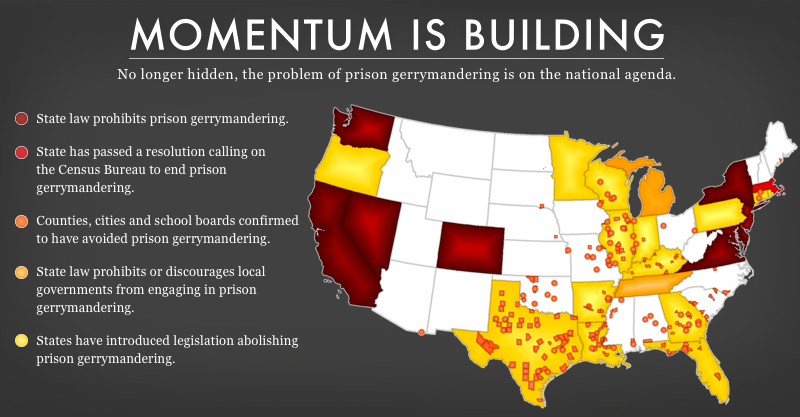

Although prison gerrymandering remains a serious issue in most parts of the United States, there is a growing movement to solve it, and significant progress toward reform has been made at the Census Bureau and at all levels of government across the country. States have the power to use correctional data to adjust Census population counts when drawing districts. Since 2010, nine states — Maryland, New York, Delaware, California, Washington, Nevada, New Jersey, Colorado, and Virginia — have passed legislation to do so, ensuring that districts are drawn with data that counts incarcerated people at home. And more than 200 counties and municipalities independently adjust their redistricting data to avoid prison gerrymandering.

All in all, over 30% of US residents now live in a state, county, or municipality that has formally rejected prison gerrymandering:

Additionally, where states have been unable to implement the most common solutions to prison gerrymandering, they have embraced other options available to them. For example, Massachusetts has not passed legislation, but it found another way to minimize the impact of prison gerrymandering when drawing districts following the 2010 Census, by specifically considering prison populations to ensure that the state would not accidentally (or purposely) concentrate prison populations within a small number of districts. The redistricting committee’s final report on their process devoted significant space to the prison gerrymandering problem and recommended that the Census Bureau create a national solution. The state legislature then doubled down on that recommendation and passed a joint resolution that officially calls on the Census Bureau to count incarcerated people at home. Notably, this solution is still available to any state that cannot pass legislation to count incarcerated people at home in time for the 2020 redistricting cycle.

These actions reflect strong public support for solving prison gerrymandering — and a push for the Census Bureau to change the way it counts in the first place. When the Census Bureau asked for public comment on how incarcerated people should be counted in 2015, over 99% of the 77,863 comments urged the Bureau to count incarcerated persons at their home address. And when the Bureau asked again a year later, almost 100,000 people voiced support for the change, including representatives from civil rights organizations, elected officials at all levels of government, former Directors of the Census Bureau, and citizens from across the country. The reform movement has also drawn editorial support from publications like the New York Times and the Philadelphia Inquirer.

In addition to legislative efforts and public comments, organizations and legislative bodies have shown opposition to the Census Bureau’s prison count and prison gerrymandering, by issuing formal resolutions and recommendations.

As a result of state and local governments’ push to avoid prison gerrymandering, as well as support from advocates and the public, the Census Bureau has recognized that the redistricting data it has historically provided does not meet the needs of those aiming to draw equal districts. Although the 2020 Census still counted incarcerated people as if they were residents of correctional facilities, the Bureau will be publishing prison population counts as part of each state’s redistricting data, making it easier for states and local governments to avoid prison gerrymandering.

As a record number of states and municipalities are poised to tackle prison gerrymandering during the upcoming redistricting cycle, now is the time to join the movement for change.