Since you asked: do opponents of prison gerrymandering want voter-only districting?

No. We oppose voter-only districting — even our recommendation that incarcerated people be excluded in some contexts lends no support to the practice of voter-only districting.

by Ginger Jackson-Gleich, December 28, 2020

Who should be counted for redistricting purposes? Since the 2010 redistricting cycle, numerous events — from the Supreme Court’s decision in Evenwel v. Abbott to President Trump’s efforts to inquire into citizenship status in the 2020 Census — have drawn attention to this important question. For people interested in our work, an additional query often follows: how exactly should disenfranchised incarcerated people be counted toward district populations?

The fact that questions persist about our recommendations for counting incarcerated people is not surprising: journalists have reported our position inaccurately; advocates for voter-only districting have tried to twist and appropriate our words; and the exclusion of incarcerated people (who generally cannot vote) is one of the solutions to prison gerrymandering that we promote in specific, limited contexts. As a result, some people assume that opponents of prison gerrymandering support voter-only districting.

In advance of the upcoming redistricting cycle, we’d like to make our position on this issue clear: we believe that all persons, whether or not they can vote, are entitled to equal representation and that everyone should be counted for purposes of redistricting. The key concern with prison gerrymandering is not whether incarcerated people should count, but where they should count. Accordingly, districting based on the eligible-voter population is not an approach that we support.

As noted above, we suspect that some of the confusion surrounding this topic arises from our recommendation that incarcerated people be excluded from redistricting data when cities or counties draw local legislative districts around correctional facilities.

To understand why such exclusion does not amount to an endorsement of voter-only districting, it is necessary to see that prison gerrymandering causes two distinct problems: it undermines equality of representation between coequal legislative districts and it siphons political power from incarcerated people’s home communities. Both issues arise from the way the Census tabulates incarcerated populations: it allocates people to their temporary prison addresses, rather than counting them at home (despite the fact that they remain legal residents of their home addresses while incarcerated).

Just like state governments, local jurisdictions — such as cities and counties — have districts that are required to contain equal populations in order to ensure equal representation by local elected officials.

However, as one federal judge has beautifully explained, city councilors, county commissioners, and other local elected officials “can’t make decisions that meaningfully affect” the people incarcerated within their districts, nor can the governing bodies to which those representatives belong do anything for such populations, whose lives are generally governed by state (or even federal) authorities. In other words, unlike other non-voter populations (like children or permanent residents), there is no “representational nexus” between local elected officials and the people detained within their districts. As a result, excluding correctional facilities when local district lines are drawn ensures that districts will have equal numbers of actual residents — and therefore that residents will have truly equal representation.

Unfortunately, local jurisdictions cannot solve the problem of prison gerrymandering in its entirety. While they can avoid creating city or county legislative districts with unequal representation, they cannot — on their own — stop the transfer of political power from people’s home communities. This is because local jurisdictions can refuse to pad their own districts with prisons (by excluding correctional populations prior to drawing district lines), but they cannot restore incarcerated people to addresses outside of their own boundaries. Accordingly, local jurisdictions cannot singlehandedly end the siphoning of political power from incarcerated people’s home communities.

Importantly, the state-level solution is different from the local one; at the state level, exclusion is neither necessary nor beneficial because states can count incarcerated people at their home addresses statewide and thereby solve both parts of the prison gerrymandering problem. Thus, for local jurisdictions, we recommend excluding incarcerated populations prior to redistricting (a partial solution being better than no solution), while our ultimate hope is that states and the Census Bureau will implement the solutions necessary to solve the problem completely.

For all of these reasons, we continue to advocate that using total-population baselines (not eligible-voter populations) is the best method for redistricting, and that incarcerated people should be counted at their home addresses. This total-population approach (sometimes described as the pursuit of “representational equality”) ensures both that elected officials represent the same number of constituents (including those — such as children, non-citizens, and incarcerated people — who cannot vote), and also that officials have a meaningful representational connection to the people they purport to represent. By contrast, efforts to ensure “voter” or “electoral equality” limit representation to only those individuals eligible to cast ballots.

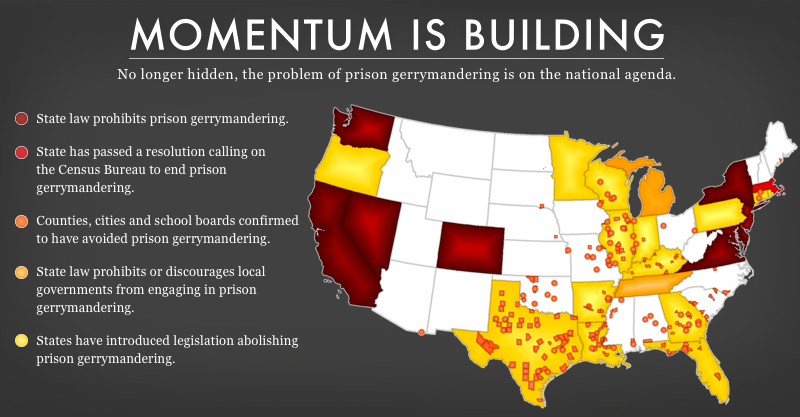

As part of our collection of updated resources for advocates, we have added a fact sheet that addresses local redistricting (and the prison gerrymandering solutions available to local governments). Readers may also wish to explore our other resources for the 2020 redistricting cycle, including a roundup of legislative solutions, as well as an explanation of why prison gerrymandering does not impact federal or state funding allocations.