New Jersey Governor signs bill ending prison gerrymandering

Over 25% of U.S. residents now live in a state, county, or municipality that has ended prison gerrymandering.

January 21, 2020

Easthampton, Mass. — Today, New Jersey Governor Phil Murphy signed a bill ending prison gerrymandering — the practice of using prisons to transfer power away from the home communities of incarcerated people, and give it to legislative districts that contain prisons. The state will now draw districts with their home, not prison, addresses.

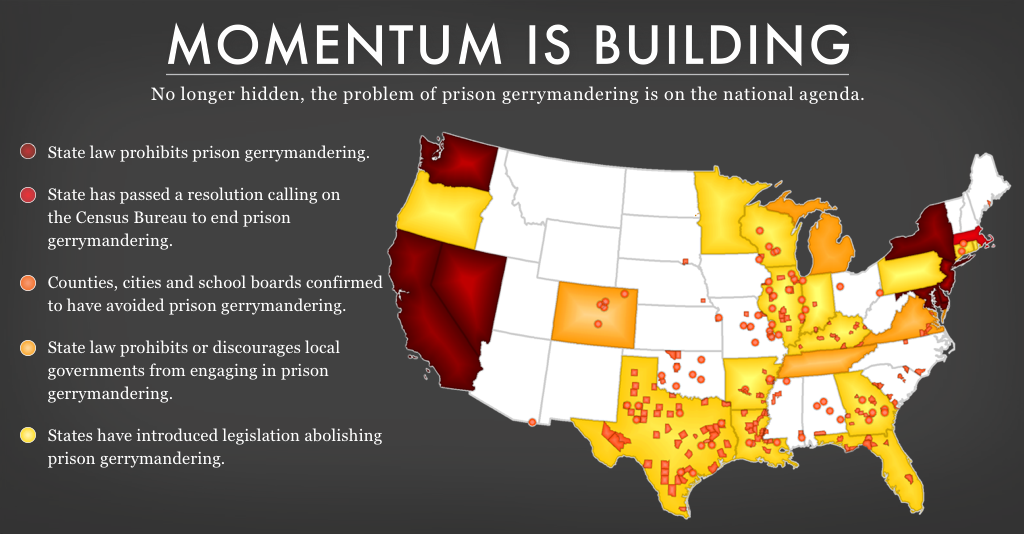

Senate Bill 758 passed the Senate in February 2019, and the Assembly on January 13, 2020. The bill, now law, caps a campaign to make New Jersey the 7th state to end prison gerrymandering and ensure equal representation for all of its residents. Over 25% of US residents now live in a state, county, or municipality that has ended prison gerrymandering. (The other states are New York, California, Maryland, Delaware, Nevada, and Washington State).

This legislative effort spanned multiple sessions and was supported by many groups, most recently including the New Jersey Institute for Social Justice and the American Civil Liberties Union of New Jersey. The bill’s sponsors included Senators Cunningham and Cruz-Perez, and Assemblymembers Sumter, Mukherji, and Quijano. The sponsors emphasized that the bill will have no effect on federal or state funds in New Jersey. All funding programs have their own data sources that do not rely on redistricting data.

“Prison gerrymandering is a fixable problem of political representation caused by the growth of prison populations in past decades,” said Prison Policy Initiative Legal Director Aleks Kajstura. Like most states, New Jersey bases its legislative districts on U.S. Census Bureau data. Unfortunately, the Census counts incarcerated people as if they were residents of the correctional facility where they happen to be on Census day. When states like New Jersey use this data for redistricting, it leads to unequal representation: People who live near prisons are given extra representation in the state legislature, while every other resident in the state receives less representation.

Senate Bill 758 is a simple state-based solution to a problem that should have been corrected by the federal government. The bill uses the state’s administrative records to reassign incarcerated people to their home addresses before redistricting. Ideally, the U.S. Census Bureau will change its policy and count incarcerated people as residents of their home addresses in the 2030 Census, but for now states should be prepared to have their own solutions in place.

New York and Maryland have already passed and implemented similar laws to count people in prison at home for this round of redistricting, and both states’ laws were successfully defended in court. California, Delaware, Nevada, and Washington State passed legislation that will take effect after the 2020 Census.

As more states take on the task of adjusting Census data to make it usable for drawing equal districts, the Census Bureau has taken some small but very helpful steps. For the first time, the 2020 Census will include correctional population data within the main redistricting dataset (the PL 94-171 file). Identifying the correctional facilities makes the data-crunching easier for states that end prison gerrymandering on their own, and will be particularly useful for states with short redistricting deadlines, such as New Jersey. This data will give redistricting officials the Census counts of people in correctional facilities at the location of the facility — enabling states to subtract incarcerated people from the prison location and, in conjunction with the state’s own home address data, reallocate them back home for that state’s redistricting.

States should follow the lead of New Jersey and Governor Murphy and end prison gerrymandering to ensure equal representation for all their residents.

Progress in ending prison gerrymandering. It is slower than we want. It is happening.