Prison gerrymandering does not impact federal aid, "there is not a straight linear relationship between state population count and federal funds flow".

by Aleks Kajstura,

August 22, 2017

Today, as happens every once in a while, a new estimate was published of how much federal funding is guided by the Census. And some folks familiar with how prison gerrymandering impacts representation start worrying whether it also impacts funding allocation. The short answer is that it does not. The long answer can be found here.

The Leadership Conference’s Counting for Dollars: Why It Matters fact sheet puts this latest analysis in context. And as the report, Counting for Dollars 2020: The Role of the Decennial Census in the Geographic Distribution of Federal Funds itself explains, per capita analyses of this type cannot be used to calculate how money follows people:

There is not a straight linear relationship between state population count and federal funds flow. The per capita figure allows cross-state comparisons of fiscal reliance on census-guided programs. It does not indicate the amount by which federal funding increases for each additional person counted.

Gov. Christie vetoes bill that would have ended prison gerrymandering in New Jersey; denies equal representation to state residents.

by Aleks Kajstura,

July 14, 2017

Resurfacing debunked arguments, Governor Christie just vetoed a bill that would have ended prison gerrymandering in New Jersey. Senate Bill 587 passed the Senate in November, and the Assembly on Monday, May 22.

The Governor’s actions perpetuate a reliance on flawed data that results in using prison populations to pad the legislative districts that contain prisons. This enhances the weight of votes cast in those districts, while diluting every vote cast by every other person in the state. In practice, prison gerrymandering uses prisons to transfer power away from home communities of incarcerated people to those who live near prisons.

The problem is amplified by New Jersey’s voting laws. Like in most states, people convicted of felonies in New Jersey cannot vote while they are incarcerated, and those who are incarcerated for misdemeanors or awaiting trial vote absentee in their home districts. This makes sense; after all, people have much closer ties to their home community than where they happen to be incarcerated on Census Day. Incarcerated people are transferred frequently between facilities, generally staying at any given facility for just 7-9 months (a fact ignored by Christie). This means that someone who votes while incarcerated is required to vote for their representative in their home district, but on paper gets counted toward as a constituent of the representative of the prison district. This mismatch creates unequal representation.

And New Jersey had already taken steps to ameliorate the effects of prison gerrymandering on school boards; extending those equal representation protections to state legislative districts was the logical next step.

Senate Bill 587 was a simple state-based solution to a problem that should have been corrected by the federal government. The bill would have used the state’s administrative records to reassign incarcerated people to their home addresses before redistricting. And to address a common misconception related to the distribution of funding (which Christie also alluded to): the bill would have no effect on the distribution of federal or state funds — all funding programs have their own data sources that do not rely on redistricting data.

Ideally, the U.S. Census Bureau will change its policy and count incarcerated people as residents of their home addresses. And last year, the Census Bureau sought comments on its current practice of counting incarcerated people at the location of the correctional facility in which they happen to be on Census day, rather than at home where they live. The Census Bureau had yet to release a final rule on where it will count incarcerated people 2020 census.

States need to take action now, on their own while waiting for the Census Bureau to correct the way it counts incarcerated people. There is still time before the next redistricting cycle for New Jersey to join California, Delaware, Maryland and New York in ensuring equal representation for their residents by ending prison gerrymandering on its own.

Recent Law Review pieces from Harvard and Stanford, conclude that prison gerrymandering is unconstitutional, question First Circuit's logic to the contrary

by Aleks Kajstura,

June 22, 2017

A full academic year has passed since the last ruling in a case that sought to end prison gerrymandering in Cranston Rhode Island, and that time was put to good use, resulting in two recent Law Review publications.

As you may recall, in Davidson v Cranston, the District Court ruled the city’s prison gerrymandering unconstitutional, reasoning that the City could not count incarcerated people in city council districts as if they were city residents while not treating them as constituents when it came time to represent them. But the First Circuit Court of Appeals reversed the decision, allowing the City to continue using the Census’ unadjusted redistricting data despite the prison miscount.

A recent Harvard Law Review case summary by Ginger Jackson-Gleich looks at Davidson and wastes no time in dismantling the First Circuit’s reliance on Evenwel in allowing prison gerrymandering.

Recently, in Davidson v. City of Cranston, the First Circuit held that the City of Cranston, Rhode Island did not violate the Equal Protection Clause by counting prison inmates as residents of one of the City’s six wards when it redistricted. To reach this conclusion, the court relied on the Supreme Court’s decision in Evenwel v. Abbott, which approved broadly of total-population-based approaches to redistricting. While Evenwel might appear to sanction Cranston’s redistricting plan, the First Circuit’s decision is at odds with Evenwel‘s underlying reasoning and emphasis on representational equality.

This quick 8-page read provides a thorough summary and analysis of prison gerrymandering through the lens of Davidson and Evenwel.

For a much deeper dive, there is a new 66-page analysis from the Stanford Law Review, The Emerging Constitutional Law of Prison Gerrymandering, by Michael Skocpol:

This Note undertakes an in-depth analysis of one-person, one-vote challenges to prison gerrymanders and is the first scholarly work to analyze this emerging body of law. It argues that the Equal Protection Clause does limit prison gerrymandering, advocating a novel approach for adjudicating these claims—one that looks principally to community ties (or the absence thereof) between prisoners and the localities that house them. It considers the impact of the Supreme Court’s recent landmark decision in Evenwel v. Abbott and other key precedents. It also discusses relevant voting rights scholarship that courts have thus far overlooked. Ultimately, this Note aims to shed light on an underexamined constitutional right—the right to equal representation, as opposed to an equal vote—and to provide courts and litigants with the tools they need to effectively tackle prison gerrymandering claims going forward.

The second half of the Stanford piece is particularly valuable for exploring the right to equal representation as a path forward in the struggle to end prison gerrymandering.

Bill to end prison gerrymandering in New Jersey has passed the Senate and Assembly, is now headed to Governor's desk.

by Aleks Kajstura,

May 25, 2017

The New Jersey legislature just voted to end “prison gerrymandering” — the practice of using prisons to transfer power away from home communities of incarcerated people and giving it to legislative districts that contain prisons. Senate Bill 587 passed the Senate in November, and the Assembly on Monday, May 22. Now it’s up to Governor Christie to sign the bill into law and end prison gerrymandering in New Jersey.

Before I delve into what this bill actually does, I’ll address a common misconception related to the distribution of funding. The bill would have no effect on the distribution of federal or state funds — all funding programs have their own data sources that do not rely on redistricting data.

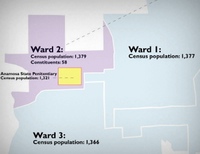

With that clarification out of the way, here is what the bill is all about: New Jersey stumbled into the prison gerrymandering problem because, like many states, bases its legislative districts on U.S. Census Bureau data. Unfortunately, the Census counts incarcerated people as if they were residents of the correctional facility where they happen to be located on Census day. This quirk in the Census data creates unequal representation when it is used for redistricting.

The unfortunate result of using prison populations to pad the legislative districts that contain prisons is to enhance the weight of votes cast in those districts while diluting every vote cast in districts without prisons.

The problem is amplified by New Jersey’s voting laws. People convicted of felonies in New Jersey cannot vote while they are incarcerated, and those who are incarcerated for misdemeanors or awaiting trial vote absentee in their home districts. This means that someone who votes while incarcerated is required to vote for their representative in their home district, but on paper gets counted toward as a constituent of the representative of the prison district. This mismatch creates unequal representation.

Senate Bill 587 is a simple state-based solution to a problem that should have been corrected by the federal government. The bill uses the state’s administrative records to reassign incarcerated people to their home addresses before redistricting. Ideally, the U.S. Census Bureau will change its policy and count incarcerated people as residents of their home addresses, but the state should be prepared to have its own solution in place for the next redistricting cycle.

New Jersey is poised to become the fifth state to pass legislation ending prison-based gerrymandering. New York and Maryland have already passed and implemented similar laws to count people in prison at home for this round of redistricting, and both states’ laws were successfully defended in court. Delaware and California passed legislation that will take effect after the next Census in 2020.

Governor Christie can now take the final step to end prison gerrymandering and ensure equal representation for all New Jersey residents.

NJ bill to end prison gerrymandering passed Assembly Judiciary Committee (already passed the Senate in November).

by Aleks Kajstura,

February 14, 2017

Yesterday New Jersey’s bill to end prison gerrymandering (A2937/S587) passed the Assembly Judiciary Committee. The bill already passed the Senate in November, and is expected to be taken up by the Assembly as early as March.