Among her other accomplishments, Jackie Berrien helped launch the movement against prison gerrymandering.

by Peter Wagner,

December 30, 2015

Last month, Jacqueline Berrien passed away at the age of 53. The NAACP LDF has an excellent essay about her life and work with lots of links to other remembrances of this important civil rights leader, but I wanted to add one more.

Before Jackie was Chair of the United States Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, she was a litigator for the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund. While there, she took a 3-year break from the LDF to work as a Program Officer for the Ford Foundation where she helped launch the movement against prison gerrymandering.

In late 2002 and early 2003, when the term “prison gerrymandering” did not yet exist and most politically savvy people had not even considered the implications of how the Census Bureau counted incarcerated people, Jackie was paying very close attention.

In October 2002, Jackie was moderating a plenary session at a large conference in Washington D.C. about felony disenfranchisement. When a panelist did not know how to respond to an audience member asking a question about the political effects of the Census Bureau’s prison counts, Jackie interjected to say that she understood that there was a new report about this problem and that its author, Peter Wagner, had signed into the conference. She invited me to stand up and introduce myself to the attendees. Many of the connections made at that conference formed the core of our work for many years to come.

In April of 2003, I was presenting my research at the Critical Resistance Conference in New Orleans, and Jackie attended my session. Even though Jackie needed to miss the bulk of my presentation, she asked the first question, a question that framed the essential strategy question for our movement:

How could an urban-dominated movement have any chance of success at getting incarcerated people counted at home if the political party that is associated with rural America currently controls all three branches of government? The answer, of course, and the foundation for the important group discussion that followed was that it shouldn’t be an urban dominated movement.

In fact, as my research showed, rural people had already been hard at work for years trying to address the problem of prison gerrymandering. Telling the stories of places like Essex County New York, and Anamosa Iowa soon became the key link in our rural and urban coalition that has won so many victories.

That June, Jackie funded a Brennan Center for Justice-organized convening of criminal justice advocates, civil rights leaders, and redistricting experts to hear the preliminary research results that Eric Lotke and I were having in our respective Soros Justice Fellowships on this topic and to decide on a collective course of action. This meeting set in motion all of the work and victories that followed.

Thank you, Jackie.

2015 saw the passing of Bertha Finn, one of the unsung heros of the movement to end prison gerrymandering. She was from Anamosa Iowa.

by Peter Wagner,

December 30, 2015

2015 saw the passing of Bertha Finn, one of the unsung heros of the movement to end prison gerrymandering. Bertha Finn, who was a retired journalist and county clerk as well as an accomplished amateur historian, was instrumental in organizing a 2007 referendum to change the form of government in Anamosa Iowa to end the practice that we later came to call “prison gerrymandering”.

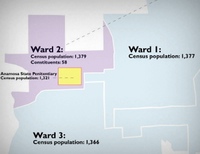

Anamosa Iowa became the symbol for the national campaign to end prison gerrymandering because the impact there was so extreme. A large prison made up just about an entire city council district. One of the few actual residents of the district was shocked to come home one day and find he’d been elected to city council by two write-in votes; one cast by his wife and the other by a neighbor.

Most people reading this blog will be familiar with Anamosa, but not Bertha’s name. She’s mentioned in only one national article, and she declined to be photographed when the Public Welfare Foundation was writing an article about Anamosa and declined to be interviewed for the prison gerrymandering segment of the Gerrymandering documentary. I don’t think she liked press attention, but on both of my trips to Anamosa she generously hosted me for conversation at her home.

In particular, Bertha filled in so many of the gaps in my knowledge about how long Anamosa residents had been aware of the problem and the efforts taken to fix it. (Most communities faced with drawing a district that would have a larger incarcerated population than resident population according to Census data would do the obvious thing and adjust the data to reflect the actual resident population. But Iowa is one of about three states where state law requires municipalities to use the Census for redistricting with no adjustments.) Eventually, Anamosa found a creative solution: it could change the form of government so that each elected official would represent the entire city.

A few years later, the city of Clarinda Iowa followed Anamosa’s lead and also abolished its wards as a way to address prison gerrymandering. My conversations with Bertha inspired a lot of my thinking about whether districts always make sense in small communities. Traditionally, districts are seen as the best way to protect the interests of minority communities, but sometimes, in very small communities, districts can unnecessarily divide up political influence. For example, Bertha correctly believed that moving to an at-large system would increase the odds that women would be elected to the city council because supportive women in other districts would be able to vote for the candidate. (For more on Anamosa, Clarinda and similar cities moving to at-large systems and some ideas on other alternative voting systems that could be helpful, see Three cities say goodbye to both wards and phantom constituents. Sadly, Bertha passed before I could share that article with her.)

While I wrote about Anamosa a lot, there was much I didn’t know and Bertha was generous with her time and memories. I learned of her February passing this Spring while were we preparing to post online a collection of clippings she had sent us years earlier from the Anamosa Gazette about the history of advocacy against prison gerrymandering in the city:

Thank you Bertha, for teaching Anamosa and the country to think outside the box when fighting for equal representation.