How many people benefit from ending prison gerrymandering?

We run the numbers. It's almost everyone.

by Peter Wagner, August 21, 2014

Prison gerrymandering dilutes your right to vote in every level of government in which it operates, so basically the entire state benefits from reform. And, counter-intuitively, some of the biggest beneficiaries of ending prison gerrymandering are rural people who live near large prisons.

First, let’s take a step back and recall two key facts:

-

Vote enhancement in the district with the largest prison dilutes the votes of the residents of every other district.

Mathematically, the impact of crediting incarcerated people to the prison districts is larger than the impact of not crediting them at home because incarcerated people come from all over the state – albeit often disproportionately from some places rather than others – but the prisons concentrate these incarcerated people to a small number of locations. This creates some vote enhancement in every district that contains a prison, but even most of those districts’ residents get less representation than people in the one district with the largest prison population.

And, the vote enhancement in the prison districts is generally so large that it disadvantages rural communities that neither contain prisons nor send very many people to prison almost as much as the typically urban district that loses the largest number of people to the Census Bureau’s prison miscount. In sum, the biggest harm from prison gerrymandering comes not from the vote dilution in the districts that send the largest numbers of people to prison, rather it comes from the larger vote enhancement in the handful of districts that contain the prisons.

-

The effects of prison gerrymandering are the most dramatic at the state and local levels of government because these districts tend to have the smallest populations.

While a cluster of large prisons typically has a negligible effect on a Congressional district of 700,000 people, the impact of a single 1,000-person prison can be massive in a county commission district of only 1,200 people. District sizes vary, but in general you can think of Congressional districts as generally being the largest, and in order of decreasing typical size, state senate districts, state house districts, county districts, and finally city districts and school boards.

So if prison gerrymandering benefits the residents of a particular district, wouldn’t that mean that every state has hundreds of thousands of people who live in such districts and have a vested interest in protecting their unearned political clout during redistricting? Actually, no.

While there are a lot of people who benefit at the state senate level, many of those same residents see larger harms at the level of the state house and local government districts.

Here are some calculations we ran last fall that illustrate how this works:

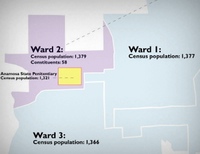

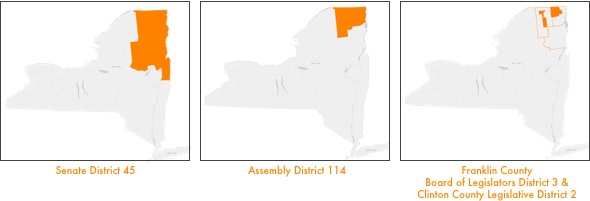

When New York was still engaging in prison gerrymandering in 2002, Senate District 45 contained 12,989 people incarcerated in state and federal prisons and was 4.34% incarcerated, giving the residents of that district extra influence in comparison with the 61 other rural, and suburban and urban districts that have no or fewer prisons within their borders. But not all residents of the 45th Senate District benefit from prison gerrymandering equally. Less than half (44%) of the district lived in the 114th Assembly District which was 6.99% incarcerated. The remainder of people who lived in Senate District 45 were in two Assembly districts that contained far fewer prison cells than the 114th.

All three counties in the 114th Assembly District contain prisons, but the vast majority (88%) of the residents of that district live in County Board of Supervisors, County Board of Legislators, or County Legislature districts that do not contain the largest prisons. New York’s decision to outlaw prison gerrymandering ended the resulting vote dilution in one or more levels of government that had been plaguing all but roughly 15,300 people in a state of 19 million. And, of course, all 19 million people benefit when the democratic process improves.

New York Senate District 45, Assembly District 114, and on the third map, Franklin County Board of Legislators District 3/Clinton County Legislature District 2. Essex County is outlined in that map but the Essex County Board of Supervisors district with the largest prison is not pictured because that district is not within Assembly District 114. Note that each of these districts may appear large on the map, but the number of people living in these areas is quite small (and the U.S. Constitution requires us to base districts on population, not land area).

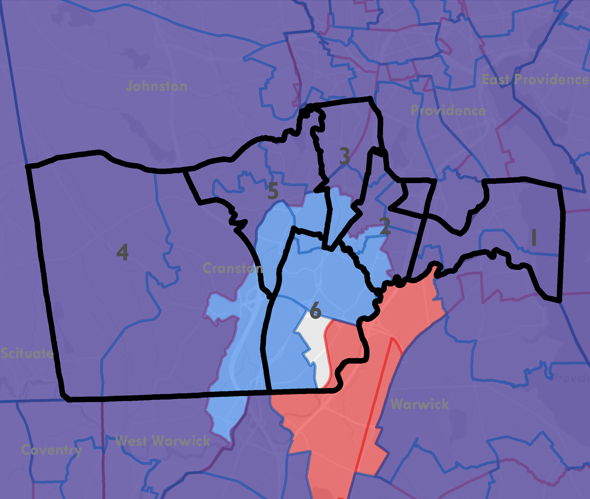

Or, to say it another way, prison gerrymandering is bad for 99.92% of the people living in New York State. And New York isn’t alone. I found the same thing when I analyzed to Rhode Island’s districts. Out of the entire state, only 112 people simultaneously live in the state senate district and the state house district with the largest prison population. Everyone else in the state has their vote diluted in one or both chambers as a result of prison gerrymandering.

This animated illustration overlays a map of all of the Rhode Island Senate districts that do not contain the largest prison populations and a map of the house districts that do not contain the largest prison populations over a map of the Cranston area.

If we superimpose the Cranston City Council Ward map over the map of the state house and state senate districts discussed above, we see that even most ward 6 residents — who dramatically benefit from prison gerrymandering at the city council — have their votes diluted in one chamber of the state legislature:

Only 112 non-incarcerated residents of Cranston Ward 6 who benefit from prison gerrymandering in the city council do not also live in a state house or state senate district where their votes are diluted by prison gerrymandering.

So what portion of Rhode Island will benefit from ending prison gerrymandering? It’s 99.989% of the people. That’s no doubt a large part of why the Rhode Island Senate last session unanimously passed a bill that would end prison gerrymandering in the state. (And why the House hasn’t passed that bill is a discussion for another day.)