New report reveals prison gerrymandering at town meeting in 7 Massachusetts towns.

October 30, 2013

For more information contact:

Aleks Kajstura

(413) 527-0845

Easthampton, Mass. – Chances are, if there’s a prison on the other side of town, your voice in town affairs is muffled.

Why? Because the Census Bureau counts incarcerated people at prison locations—where they neither vote nor reside— rather than at their home addresses. When governments use this data to draw electoral districts, they grant undue political power to people who live near prisons and dilute the votes cast everywhere else. Although not always intentional, this “prison gerrymandering” often results in significant voting inequality. A new report from the Prison Policy Initiative, reveals that the Census Bureau’s counts of incarcerated populations lead 7 Massachusetts towns to dilute the votes of residents who do not live in the precinct that contains a correctional facility.

In both Ludlow and Plymouth, for example, 35% of a precinct’s representatives at town meeting are attributed to the jail population. That gives any 65 people who live in those precincts the same voice at town meeting as 100 residents from any other precinct.

These phantom constituents inflate the voice of the actual residents of that precinct and in turn dilute the votes of any resident in other precincts. “When the first town meeting in the United States was held 380 years ago in Dorchester, prison counts were probably the last thing on the participants’ minds,” said report author Aleks Kajstura. “But today, the way the Census Bureau counts people in prison is a big problem for the principle of ‘one person one vote.'”

The towns of Billerica, Dartmouth, Dedham, Framingham, Ludlow, Plymouth, and Walpole each contain a precinct where 17% to 35% of the precinct’s representatives are directly attributable to the Census Bureau’s prison miscount, finds the report.

“For most of these Massachusetts towns, the Census Bureau’s prison miscount just wasn’t on the radar,” Kajstura said. “But fortunately, towns can make simple adjustments to keep the Bureau’s prison counts from distorting local democracy.” The report concludes that even though the problem of prison gerrymandering originates from the Census Bureau’s methodology, towns can take action to address prison gerrymandering.

Additionally, a resolution calling on the Census Bureau to solve the problem nationwide by agreeing to tabulate incarcerated people as residents of their home addresses in the decennial census is currently pending in the Massachusetts Legislature, and just passed out of Joint Committee on Election Laws. The new Director of the Census Bureau, John Thompson, recently stated that he has not yet decided how prison populations will be counted in the 2020 Census.

Massachusetts Resolution S 309/H 3185 passed joint House and Senate Election Laws committee, moves on to the committee on Rules.

by Aleks Kajstura,

October 22, 2013

A Massachusetts resolution (S309/H3185) urging the Census Bureau to end prison gerrymandering by counting incarcerated people at their home addresses just passed out of the Joint Committee on Election Laws. In March, the Prison Policy Initiative joined other supporters to testify before the committee in support of the resolution.

The resolution now heads to the Joint Committee on Rules.

More than half of the incarcerated people in Ohio come from just 6 populous counties, but more than half of the state's prison cells are located in just 6 small counties

by Peter Wagner,

October 10, 2013

I just completed a remote presentation about our research on prison gerrymandering in Ohio. While preparing my talk, I discovered a new way to explain our map and data table about where incarcerated people come from and where they go in Ohio. In a sentence:

More than half of the incarcerated people in Ohio come from just 6 populous counties, but more than half of the state’s prison cells are located in just 6 small counties:

And if you are intersting in bringing PPI speakers to your organization — in person or remotely — please get in touch.

The federal government, in the form of the Census Bureau, is permitting states and counties all over the country to undermine the "one person, one vote" concept.

by Peter Wagner,

October 8, 2013

A new blog post by Andrew Cohen at the Brennan Center for Justice reviews the struggle to end prison gerrymandering, adding some great historical context:

Fifty years ago, in two vital cases you don’t hear much about anymore, the United States Supreme Court set forth a “one person, one vote” standard for legislative redistricting that we all think we live under today….

Now let’s jump ahead half a century for a lesson in how even the Court’s noblest endeavors can be undermined by practical realities. The federal government, in the form of the Census Bureau, is permitting states and counties all over the country to undermine the “one person, one vote” concept.

His piece then goes on to discuss some of the new developments in the movement to ensure that the Census Bureau listens to the state and local governments that are calling for a national end to prison gerrymandering, and agrees to tabulate incarcerated people as reidents of their home communities in the next census.

Thanks, Andrew!

(For more of Andrew’s great updates and reporting on criminal justice issues, follow him on Twitter, and check out the other pieces he’s written for the Brennan Center for Justice and for The Atlantic.)

New fact sheet highlights prison gerrymandering in Ohio after the 2010 Census.

by Aleks Kajstura,

October 3, 2013

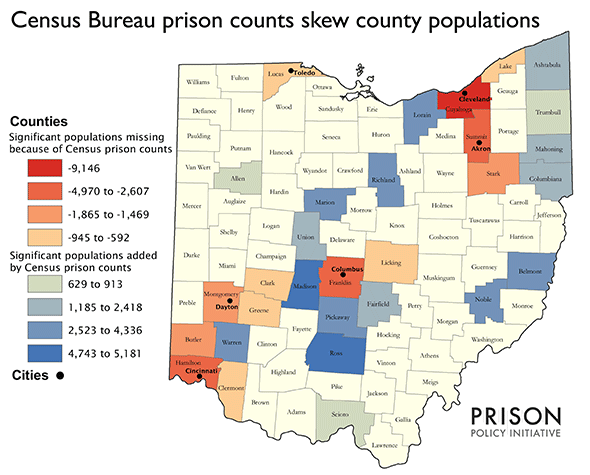

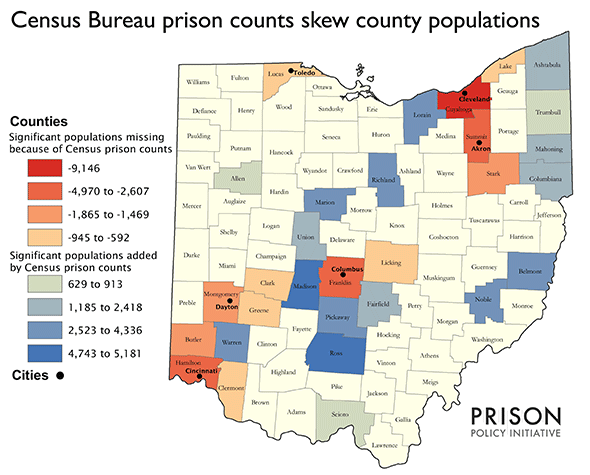

We have a new fact sheet highlighting the problem of prison gerrymandering in Ohio after the 2010 Census. The Census Bureau’s practice of counting incarcerated people as if they are residents of the prison, rather than their home address, continues to have a major impact on voting equality in Ohio, where there are 15 state House districts and 8 Senate districts padded with significant incarcerated populations.

The map below shows how the Census Bureau’s prison count moves incarcerataed people across county lines (for more detail, see the table at the end of this post):

Continue reading →