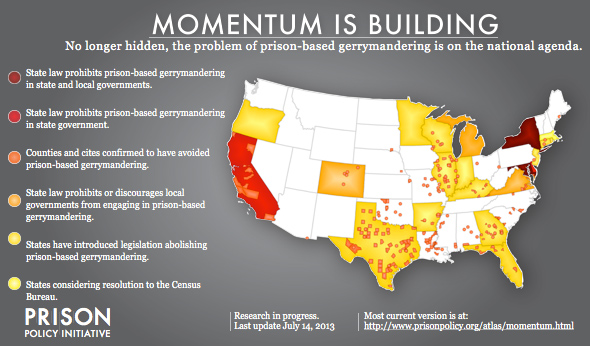

Thanks to your support, we've put the problem of prison gerrymandering – and the solutions -- squarely on the national agenda.

by Peter Wagner,

December 21, 2012

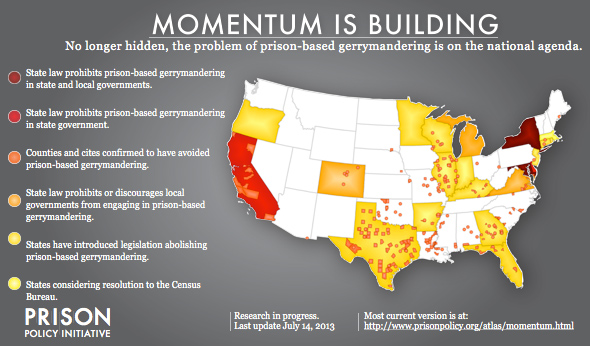

It’s happening! The national movement to end prison-based gerrymandering took huge strides forward in 2012. Some of the victories were easy to see, like in June when the Supreme Court upheld Maryland’s first-in-the-nation law that did what the Census Bureau had refused to do: count incarcerated people as residents of their homes for redistricting purposes.

Other victories were more subtle, like when the Maryland victory this summer finally energized the editorial boards of the Hartford Courant and the Norwich Bulletin to criticize the Connecticut legislature for twice failing to pass the bill to end prison-based gerrymandering, and to demand that the legislature pass it in the next session.

And flying under the national radar are the more than 200 rural counties and cities that have taken a stand against prison-based gerrymandering when drawing county and municipal districts. Impediments to further reform are falling quickly. For example, this year the Virginia legislature unanimously changed state law to give more counties in that state the option to avoid prison-based gerrymandering.

A decade ago, the problem of prison-based gerrymandering was almost entirely hidden. Today, thanks to your support, we’ve put the problem – and the solutions — squarely on the national agenda. Your moral encouragement and financial investment has helped to build my law school project into a national movement that is permanently improving how our democracy works. The research and the outreach you helped fund has enabled us to build a network of hundreds of organizational allies and elected officials across the country, and has won us the ear of the Census Bureau.

As I describe in my Washington Post op-ed, the next Census in 2020 sounds far away, but the key planning is underway now. Together, our movement is making sure that the handful of legislative districts with prisons will no longer be able to dominate the political process.

Our research and advocacy – and this blog – is at the center of this national movement. Our support comes from two foundations and a small network of individual donors. Can you join those donors in making a tax-deductible contribution to support our work today? Thank you for being part of this movement!

Drew finds a great way to explain who loses and who benefits from prison-based gerrymandering in his home state of North Carolina

by Drew Kukorowski,

December 19, 2012

Editor’s note: Drew prepared this article shortly before he wrapped up his work with us last week. We’re grateful for the huge contributions he made! -Leah Sakala

Here at Prison Policy Initiative we’re always trying to think of better ways to explain the problem of prison gerrymandering to folks who may not have heard about it before. Prison gerrymandering is the practice of counting incarcerated people as residents of the prisons that detain them, and then using those numbers when election districts are redrawn in order to comply with the Supreme Court’s one person-one vote requirement.

When I first heard about this “miscount,” I wasn’t sure exactly who was harmed by it. Normally, we think that living next door to a prison is undesirable; in this situation, though, living next door to the prison is highly beneficial. That’s because the votes of people who live next door to a prison carry more weight than the votes of people who live in non-prison districts. I’m from North Carolina, and there’s a great example of this problem back home that helped me understand the harm caused by prison gerrymandering.

There’s only one federal prison in North Carolina. But it’s a big one — FCI Butner just north of Durham in Granville County. In 2010, the Census counted about 4,500 people as residents of the Butner prison complex. But none of those incarcerated people can vote, and the vast majority don’t come from North Carolina, much less from Granville County (e.g., Bernie Madoff). Nonetheless, the Census counts them as residents of Granville County, and the county used those numbers to balance their county commissioner and school board districts during the last round of redistricting.

In the example I found, the people who live near the federal prison in Granville County get twice as much political influence as people who don’t. The Granville County commissioner and school board district — District 3 — with the big federal prison complex is about 50% incarcerated (52.5% to be exact). This is a huge benefit to the actual residents of District 3, but harms the residents of every other district in the county. That’s because the commissioner and school board member from the prison district only have to serve about 4,000 actual constituents. In all the other districts in the county, though, the commissioners and school board members each serve about 8,500 constituents. This means that you have less access to your elected representatives if you don’t live in the prison district. Or to put it another way, every 47 residents of the prison district have as much political power as 100 residents in other districts.

Smaller but still important is the effect of prison gerrymandering on state representative and senatorial districts. Newly drawn NC House District 2 is about 6.7% incarcerated if you take into account the federal and state prisons in Butner (there’s a state prison across the street from the federal prison that has about 1,000 inmates). And the new NC Senate District 20 is about 3% incarcerated. Again, the residents of those districts have more access to their state representatives because those representatives don’t have as many real constituents to serve as the representatives from districts without prisons.

While Granville County didn’t address its prison gerrymandering problem this time around, maybe it will in 2020. After all, there are more than 200 counties and cities around the country with prisons that decided not to use the prison populations when redrawing their district lines. To be fair, Granville County is required to submit its redistricting changes to the U.S. Department of Justice under the Voting Rights Act, and it was concerned that removing its prison population might raise a red flag with the U.S. Department of Justice. But of the 200 counties and cities that avoided prison gerrymandering, about 90 were required to have their plans approved by the U.S. Department of Justice, and all received that approval. Or maybe the North Carolina General Assembly will pass legislation – like Maryland and New York, have – mandating that state and local governments draw election districts based on their real populations. Maybe if Mr. Madoff runs for that school board seat then Granville County will realize that it’s absurd to count prisoners as local residents.

The Report from the Chairs of the Special Joint Committee on Redistricting concludes that action at the Bureau is the "most expedient and streamlined avenue" towards ending prison gerrymandering.

by Peter Wagner,

December 12, 2012

The Co-Chairs of the Massachusetts Special Joint Committee on Redistricting today issued a report reviewing their accomplishments and their recommendations on issues they discovered while redrawing the Massachusetts district lines.

Senate Chair Stanley Rosenberg and House Chair Michael J. Moran devote about a quarter of their report to reviewing the vote dilution caused by the Census Bureau’s decision to tabulate incarcerated people as residents of the prison location instead of at their legal home addresses. The current system, the report observes, “inflates the relative strength of votes by residents in that district [containing a prison] at the expense of voters in all other districts in the Commonwealth.”

The co-chairs discuss the unique requirements of the Massachusetts constitution, noting that it would be theoretically possible to propose a constitutional amendment that would allow the state to end prison gerrymandering by state legislation. They conclude, however, that the “most expedient and streamlined avenue” towards a solution is for the Census Bureau to tabulate incarcerated people at their home addresses. Action at the Census Bureau would ensure a “systematic and consistent tabulation approach” that would relieve legislatures of the burden of each adjusting their own redistricting data.

The message is clear:

“The tabulation of prisoners should be at the forefront of Bureau priorities in evaluating and adjusting how the 2020 U.S. Census will be conducted.”

“We agree that the way prisoners are currently counted does a disservice to the state and should be changed.”

But the co-chairs did not intend the report to be the final word on the matter. The very first recommendation in the report is a call for the Massachusetts legislature to:

“Pass a resolution by the General Court requesting that the U.S. Census Bureau change the residency classification for counting prisoners at their legal residence prior to incarceration. The Legislature could consider a constitutional amendment in the event the federal government does not act on our recommendations.”

For more information, see:

The movement to end prison gerrymandering had its best year ever in 2012. Can you help us keep the momentum up in 2013?

by Peter Wagner,

December 7, 2012

The movement to end prison gerrymandering had its best year ever in 2012. Can you help us keep the momentum up in 2013?

Our biggest victory was widely-publicized when the Supreme Court upheld Maryland’s first-in-the-nation law ending prison gerrymandering. We won a quieter victory when the Virginia legislature unanimously changed state law to give more counties in that state the option to avoid prison gerrymandering. And you saw in last week’s newsletter that more than 200 rural counties and municipalities have responded to the call to end prison gerrymandering in their own districts.

Our research and advocacy – and this newsletter – is at the center of this national movement. Our support comes from two foundations and a small network of individual donors. Can you join those donors in making a tax-deductible contribution to support our work today? Thank you for being part of this movement!

by Aleks Kajstura,

November 27, 2012

Peter Wagner, our executive director, is in Kentucky today testifying about BR 219, a bill to end prison gerrymandering, before the Kentucky General Assembly Task Force on Elections, Constitutional Amendments, and Intergovernmental Affairs. In addition to explaining how prison populations in redistricting data distort state legislative districts, Peter will highlight how Kentucky counties grapple with prison gerrymandering when drawing their magisterial districts. For more information about prison gerrymandering in Kentucky and how you can get involved, check out our Kentucky campaign page.

Ever since redistricting season started, we've been researching how local governments across the country have handled the problem of prison-based gerrymandering. Our results? A clear trend away from prison-based gerrymandering.

by Leah Sakala,

November 26, 2012

How do officials in cities or counties that contain large prisons draw their electoral districts? Do they accept Census Bureau data that inflates the population of the area containing the prison, or do they reject the Census Bureau’s prison counts in order to draw fair districts?

We’ve been reaching out to cities and counties across the country, first to bring the problem of prison-based gerrymandering — and the solutions — to their attention, and then more recently following up to see what they did. We’re happy to report that we’ve found that most of these cities and counties exclude the prison populations in order to give all of their actual residents the same access to government.

Just the other day, we hit a big milestone in the project when we verified the 200th county or city to refuse to engage in prison-based gerrymandering: Prison Policy Initiative Legal Director Aleks Kajstura found that Howard County, Texas refused to use the 5,000+ people in private and federal prisons when drawing its new County Commissioner precincts. Had county officials engaged in prison-based gerrymandering, the First Precinct would have been more than 60% incarcerated, giving every four residents of that precinct the same influence as ten residents in any other parts of the county.

This milestone in our research is further evidence that the national trend away from prison-based gerrymandering is gaining momentum. And even more exciting is the fact that 200 is a significant underestimate of the number of local governments that avoid prison-based gerrymandering. We know that the actual number is much higher, in part because we’re still calling counties and because redistricting is not yet complete in some locations, but especially because we’ve largely skipped following up in states that require counties and municipalities to exclude prison populations. Instead, we’ve focused on the places that must independently choose whether or not to avoid prison-based gerrymandering. And there, the trend is clear: prison-based gerrymandering is on the decline.

To celebrate reaching 200, we’ve updated our map of national progress towards ending prison-based gerrymandering:

These 200+ communities deserve the credit for finding creative solutions to the unexpected problems caused by the Census Bureau’s archaic method of tabulating incarcerated people. Unfortunately, often unknowingly, many other communities used census counts of prison populations to dilute the votes of most of their own residents. Hopefully the Census Bureau will update its methodology and present the country with a national solution by counting incarcerated people at home in 2020.

While President Obama is hoping for a victory in Ohio on Tuesday, Lima residents have already won a democratic victory of their own over the problem of prison-based gerrymandering.

by Leah Sakala,

November 2, 2012

As you’ve probably noticed, I’ve been keeping close tabs recently on the presidential candidates’ travel itineraries. As they jet around the country to drum up votes in Tuesday’s election, they keep making campaign stops in cities and counties where prison-based gerrymandering presents a major democratic challenge.

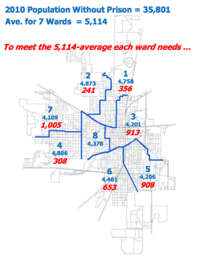

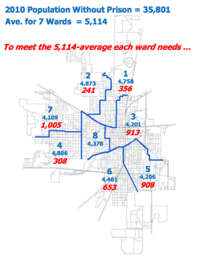

This afternoon, President Obama will be speaking to a crowd of voters in Lima, Ohio. While the president is hoping for a victory in Ohio on Tuesday, Lima residents have already won a democratic victory of their own over the problem of prison-based gerrymandering. For more than two decades, officials in the City of Lima have refused to pad their city wards with the populations of the two state prisons located within city limits.

As Board of Elections Director Keith Cunningham explained, the decision to exclude incarceration populations makes sense because “prisoners have no communications, no voting rights, and are not a constituency.” If city officials had not adjusted the 2010 Census data by removing the prison populations for redistricting purposes, about half of the population in Ward 1 would have been made up of people in the state prisons. By avoiding prison-based gerrymandering, the city ensured that the actual residents of Ward 1 were not granted twice the voting power of any resident in the other six districts.

So, although Obama may not mention prison-based gerrymandering this afternoon, the City of Lima has a strong history of maintaining a healthy democracy. And on Tuesday, Lima voters will have the opportunity to exercise it again.

The state needs to take action to ensure that phantom constituents don't continue to distort local democracy.

by Leah Sakala,

November 2, 2012

As the number of undecided voters wanes in the week before the presidential election, the candidates are making a last push to garner support in swing states. Earlier this week, vice presidential candidate Paul Ryan returned to his home state of Wisconsin to rally for the Romney ticket and to go trick or treating with his kids. But when he rallied in Racine, Wisconsin on the afternoon of Halloween, the voters had more to be scared of than just a spooky holiday. While Racine voters should carefully consider who to vote for in the national election next Tuesday, they should also be concerned about the phantom constituents in their midst that are skewing local democracy.

These phantom constituents were created when the county redistricted based on Census data that counted the people locked up in several state prisons as though they were actual residents of Racine County, rather than in their home communities. As as result, nearly one-fifth of District 14 can only be found by looking behind bars and the real residents of District 14 reap the extra political clout from the phantom constituents. Each vote cast in District 14 is 19% more powerful that a vote cast in another district. Consequently, everyone else’s vote is worth less.

At redistricting time last year, Racine County Supervisor Ken Lumpkin was certainly worried about counting incarcerated people as county constituents. As he pointed out, “It’s unfair [that prison populations] are utilized in the census count. They are not active participants in the community.” In the end, though, the prison population was left in the redistricting data despite Supervisor Lumpkin’s concerns.

Fortunately, the Supreme Court’s recent endorsement of Maryland’s law ending prison-based gerrymandering has given Wisconsin legislators the green light to move forward on a state-wide legislative solution. By passing a bill to end prison-based gerrymandering in state and local districts, Wisconsinites would be able to rest assured that phantom constituents don’t haunt elections for decades to come.

What would candidates say about how they plan to take action on the problem of prison-based gerrymandering?

by Leah Sakala,

October 26, 2012

With election day less than two weeks away, candidates are ramping up the effort to get out the vote in swing states like Ohio. Earlier this week, vice president Joe Biden made a stop in the city of Marion, Ohio to rally support among Marion voters.

But while all residents of Marion can play an important role in the outcome of the national elections, some voters have almost four times the political clout of others in city elections. Why? Because it’s one of the most dramatic examples of prison-based gerrymandering in the country.

When officials in the City of Marion started redistricting after the 2010 Census, they already had a prison-based gerrymandering problem. Two city wards were padded with state prison population, giving an unfair 30% boost to the votes cast by residents in those districts.

But rather than remedy the problem in the most recent round of redistricting, it got worse when both prisons were placed in the very same ward. Today, nearly three-fourths of the population in Ward 1 is made up of people in the state prison, giving one resident in that ward the same access to local government as 4 people in any other ward.

I wonder what Vice President Biden would have said if a Marion resident at the rally had asked him how his administration plans to protect her vote from being diluted due to the Census Bureau’s prison count?

The National Advisory Committee on Racial, Ethnic and Other Populations can pass a resolution calling on the Census Bureau to take action.

by Leah Sakala,

October 26, 2012

Ben Peck of Dēmos testified this morning before the Census Bureau’s National Advisory Committee on Racial, Ethnic and Other Populations, explaining why it’s time for the Census Bureau to plan ahead to end prison-based gerrymandering in 2020 once and for all.

Now is the time, Ben explained, “for the Bureau to undertake the evaluation and research that will be necessary to change its practices for determining the residence of incarcerated persons, so that in the next Census incarcerated persons will be properly tabulated as residents of their home communities.”

Subcommittees of the Race and Ethnic Advisory Committee to the Census Bureau have repeatedly passed resolutions urging the Bureau to take up this research issue:

- Recommendation 2: Residence Rule, African-American subcommittee of the Census Bureau’s Race and Ethnic Advisory Committee, October 2011.

“The Committee recommends that the Census Bureau prioritize conducting research as part of their 2020 Census planning to describe a process and the feasibility of implementing changes to the “usual residence” rule to provide a count in the 2020 Census of incarcerated persons at the pre-incarceration addresses, including identifying the best means of gathering such information and incorporating it into Census counts nationwide.

- Recommendation 3 — Research on Alternative Methods of Counting Prisoners, Joint Resolution of the Hispanic and Asian-American subcommittees of the Census Bureau’s Race and Ethnic Advisory Committee, October 8, 2010

- Recommendations focused on 2020, African-American subcommittee of the Census Bureau’s Race and Ethnic Advisory Committee, October 2009.

“The AA REAC recommends the Census Bureau allows prison inmates to fill out individual census forms giving their own preference as to place of residence, rather than continuing the current practice of having the prisoners counted as group quarter’s population where they are incarcerated.

The AA REAC recommends the Census Bureau provides an opportunity to discuss the topic of prisoners… and political representation in the communities from which they came.”

- Recommendation 10, Census Advisory Committee of the African-American population, October 1-3, 2003:

“We recommend that prisoners, including those housed outside their states, be counted as residents of their pre-incarceration addresses…”

The Census Bureau made great progress for the 2010 Census by publishing correctional population data in time for state and local governments to avoid prison-based gerrymandering by making populations adjustments on their own. The National Advisory Committee on Racial, Ethnic and Other Populations now has the opportunity to urge the Census Bureau to keep making progress on this issue. After all, as Ben points out, only the Census Bureau has the power to put an end to prison-based gerrymandering nationwide:

Fortunately, the Census Bureau can achieve a full and permanent solution for the 2020 Census: revising its “usual residence” rule to tabulate incarcerated persons as residents of the community where they resided prior to incarceration.