Similarities in counting overseas Americans and counting prisoners at home

by Peter Wagner, February 9, 2004

On February 5 2004, the Census Bureau began a test enumeration of Americans in France, Mexico and Kuwait to determine the feasibility of counting all overseas Americans in the 2010 Census. Whether and how to count this population, now estimated at 4.1million, has long been a contentious issue because of the difficulty in locating overseas Americans and in determining whether overseas Americans should be assigned to particular stateside addresses. The debate over overseas Americans offers some guidance on the prisoner-counting question because it shows that the usual residence rule has evolved over time and that questions of necessity, impact, and feasibility shape the rule’s evolution. In sum, a modern Census of a modern America requires a complete count of the nation’s prisoners and it requires that count to be of the prisoners at their home addresses.

First, the “usual residence rule”, which requires prisoners to be counted at the prison and requires that most overseas Americans be excluded from the count, is not fixed in stone. The rules for overseas Americans have changed a number of times, as illustrated by the below chart prepared by the Census Bureau in 1993 and updated by PrisonersoftheCensus.org in 2004.

Residence Rules Pertaining to Americans Overseas: 1870-2000

Beginning in 1820, census takers were supplied with printed instructions to clarify who should be enumerated in their district. Census years not listed below did not include residence rules for the overseas component.

U.S. Military Personnel Stationed Abroad or at Sea

- 1870, 1880, 1900:

- Enumerate at stateside home (also may have been included in overseas population in 1900)

- 1910-2000:

- Do not enumerate at stateside home (included in overseas population)

Federal Civilian Employees Stationed Abroad

- 1900:

- Enumerate at stateside home (also may have been included in overseas population)

- 1910-30, 1950-2000:

- Do not enumerate at stateside home (included in overseas population)

Crews of U.S. Merchant Marine Vessels at Sea

- 1870, 1880, 1910, 1920:

- Enumerate at stateside home (not included in overseas population)

- 1930, 1940:

- Enumerate officers at stateside home. Do not enumerate crews at stateside home. All merchant vessels were homeported, regardless of location, so crews were not included in overseas population

- 1950-90:

- Do not enumerate at stateside home 1950, 1960: included in overseas population if vessel was at sea or in a foreign port 1970: included in overseas population if vessel was at sea with a foreign port as its designation or in a foreign port 1980: not included in overseas population 1990: included in overseas population if vessel was sailing from one foreign port to another or in a foreign port 2000: not included in overseas population

Private U.S. Citizens Abroad for an Extended Period

- 1910-40:

- Enumerate at stateside home (not included in overseas population)

- 1960-2000:

- Do not enumerate at stateside home (included in overseas population only in 1960 and 1970)

As the Census Bureau wrote:

“A major observation that emerged from reviewing these historic materials [to prepare the table] was the lack of a single conceptual thread running through the censuses concerning how Americans abroad fit into the overall decennial enumeration. It was partly this absence that led to the inconsistencies.” (Americans Overseas, page 1.)

Second, political and societal changes in the United States were key factors in the evolution of the usual residence rule for overseas Americans. A review of these same factors requires a change in the rule to count prisoners at their homes and not in the prisons.

Basic feasibility

Overseas Americans are hard to locate. Americans overseas are not required to register their locations with the State Department or local governments, so there is no master list of overseas Americans. This problem is what the Census Bureau’s overseas American test enumeration hopes to answer. Prisoners, on the other hand, are under the complete control of the state. The Census already has experience counting the prisoners themselves, although not in assigning them to their home geography.

Necessity due to demographic change

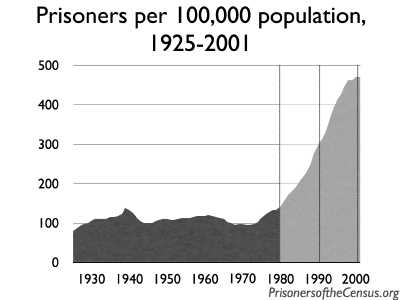

The 1980 Census was the last Census taken before incarceration rates began to skyrocket.

The 1980 Census was the last Census taken before incarceration rates began to skyrocket.

World War II and the Vietnam War meant an increase in the numbers of Americans overseas and an increased relevancy in counting them. After the Vietnam War ended, the number of overseas Americans fell along with the imperative to count them. Prisoners, on the other hand, used to be a very small population, but now constitute a group larger than our three smallest states combined.<.span> Accurately counting this population at home is quite relevant to accurately portraying our society and communities.

Who do we count?

Counting overseas Americans is complicated by definitional issues. Should all American citizens be counted or just those who intend to return home? Should American-born persons who are now citizens of other countries be counted? What about those who are U.S. citizens but lack a financial tie to the U.S. via Social Security or employment for a U.S. company? All of these possibilities have benefits and drawbacks. With prisoners, the answer is as clear and uncontroversial as it is simple: Count them at home.

Unanswered questions as to where to count the population and why

Some Americans are overseas in the furtherance of U.S. government and corporate interests. Other Americans are overseas for personal reasons. Some of these individuals intend to return, and some do not. It can be assumed that most military personnel intend to return, but it is hard to guess the intentions of non-military personnel. Prisoners are quite different. They are present in the prisons involuntarily. It can safely be assumed that prisoners will not choose to remain at the prison when their sentences are completed. Six hundred thousand people are released from U.S. prisons or jails each year, and almost all of the 2 million incarcerated people will eventually leave prison and return home. The median time served before first release for state prisoners is 53 months and for federal prisoners, 18 months. But nobody can guess when — or where, or even if — overseas Americans will return home.

Do sufficient administrative records exist to assign individuals to a geography below the state level?

In a number of Censuses and for certain population groups, the state level overseas population data was provided to the Census from government administrative records that did not include street addresses. As a result, the Census was able to assign individuals to states for purposes of congressional reapportionment, but was not able to determine where these individuals should be counted for redistricting purposes. In other decades and with other populations, this issue was a factor in preventing the Census from counting the overseas groups at all. With prisoners, the Census has many more options. All prisoners are currently enumerated using special forms and procedures, and these forms could be modified to ask prisoners to declare a home address rather than require them to report the facility address. Alternatively, or in the limited circumstances where Census forms are completed administratively by Department of Corrections personnel, the anticipated release address or address at time of arrest could be used. The data exists to completely and accurately count prisoners without any of the difficulties implicit in the counting overseas Americans and assigning them to a specific stateside geography.

Can the count be done accurately?

The “standard review and quality control procedures” applicable to stateside censuses are inapplicable to the “decentralized and globally far-flung nature of these overseas [counting] operations.” (Americans Overseas, page 4.) For example, unlike the stateside census, the Census would be unable to judge completeness of responses against a master address list for the country. Prisoners are far easier. The Census Bureau knows in advance how many prisoners exist and where to send the forms. A complete count can be readily assured for prisoners, with only one question remaining: Where should they be counted? Telling prisoners to declare their own addresses would be a simple solution with none of the complexity involved in locating overseas Americans and assigning them to stateside addresses.

Will it make a difference?

If there will be no impact, changing Census procedures would probably be ill-advised. The expected outcome has often determined the counting mechanism, although there have been surprises. It was expected that the overseas count was proportionate to the state population counts, and therefore should have no impact on congressional reapportionment. But the 1970 overseas count shifted a congressional seat from Connecticut to Oklahoma by a margin of less than 300 people. (Americans Overseas, page 4.) And as the Prison Policy Initiative‘s research on its site and this website have indicated, the consistent overrepresentation of urban prisoners in rural prisons has a profound impact on state legislative redistricting.

Conclusion

Whether and how to count overseas Americans is a complicated issue that the Census Bureau hopes will be clarified by its test enumeration that began last week. But looking at how the Census Bureau has approached the overseas Americans issue suggests that our system of government requires prisoners to be counted at their home addresses and not at the prisons. This may not have always been the case, but today, with 2 million predominantly urban and minority people behind bars in predominantly white and rural towns, our democracy requires it.

Americans Overseas in U.S. Censuses by Karen M. Mills, U.S. Census Bureau, November 1993, Technical Paper No. 62.

Census Bureau Begins Overseas Census Test U.S. Citizens in Three Countries to Be Counted U.S. Census Bureau Press Release, February 5, 2004.

Bureau of Justice Statistics, Sourcebook of Criminal Justice Statistics, 2001, Tables 6.39 and 6.52