by Peter Wagner,

August 18, 2003

The Federal Constitution does not prohibit a state from adjusting the census data to count population as it wishes the prisoners to be counted:

“Although a state is entitled to the number of representatives in the House of Representatives as determined by the federal census, it is not required to use these census figures as a basis for apportioning its own legislature. (Borough of Bethel Park v Stans, 449 F.2d 575 (3rd Cir. 1971)

When the 2000 Census made mistakes and counted some prisons in empty fields or in the middle of the Hudson River, New York corrected its Census-based redistricting data by “moving” the prisons back to their actual locations. A special state census of all residents would be one way to accurately count the population of prisoners at their legal residences. Alternatively, a state could adjust the federal Census data to transfer each prisoner’s Census count from the prison town to his or her legal residence.

by Peter Wagner,

August 11, 2003

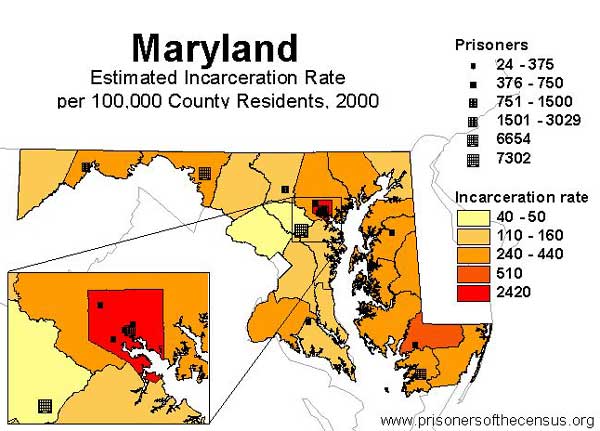

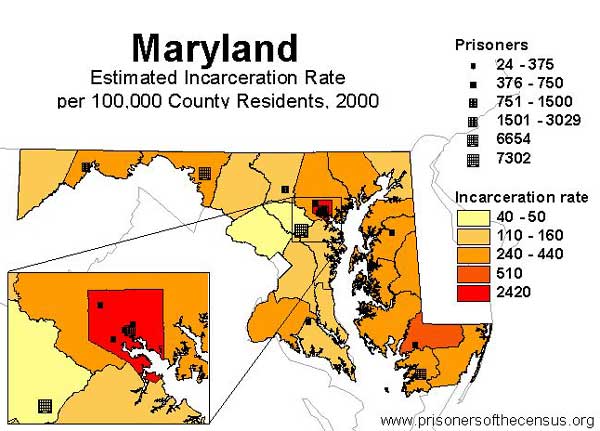

There is a tremendous disparity in Maryland between the incarceration rates in each county. Baltimore City’s incarceration rate of 2,420 per 100,000 residents may be the highest incarceration rate of a city in the country. (By comparison, in 1950 the Soviet gulags held 1,423 prisoners per 100,000 residents.) Although the bulk of the prisoners come from Baltimore City, most of the prisons are constructed far from the city.

The enumeration of prisoners from Baltimore as if they were residents of these prison communities decreases the political power of Baltimore and increases that of the prison regions.

The enumeration of prisoners from Baltimore as if they were residents of these prison communities decreases the political power of Baltimore and increases that of the prison regions. As a result, Baltimore does not get the legislative attention it so desperately needs.

by Peter Wagner,

August 4, 2003

As the following two letters to the editor show, counting prisoners as residents of the prison town can present an image of rapid growth or tumultuous decline, when in fact nothing has really changed:

The Census could protect our communities from artificial swings in population if they counted prisoners at home and not in temporary prisons.

Dear Editor, Youngstown Vindicator According to your recent article “Valleys are still losing people” almost half of the population lost in Mahoning County since Census 2000 is “misleading and explainable” due to the closure of a private prison in Youngstown. The purpose of the census is to count residents in each community, so those prisoners should never have been counted at the prison in the first place. When a community reports a large decline in population, it looks unattractive for potential development.

The Census could protect our communities from artificial swings in population if they counted prisoners at home and not in temporary prisons. Peter Wagner, Prison Reform Advocacy Center Cincinnati, OH July 16, 2003

Dear Editor, Birmingham NewsYour article “Brent is booming, behind iron bars” (July 18) reports all of the town’s reported population increase was the result of an increase in the prison population at the Bibb County Correctional Facility. Alabama’s second fastest growing town is, well, not actually growing. According to the Alabama Department of Corrections, only a few of the prisoners at the Bibb County prison are from Bibb County. But the 1,800 prisoners are more than 8% of the county’s population. The purpose of the Census is to reflect the size, strengths and needs of our communities. It would make more sense for the Census to count prisoners at home rather than pretend they lived as permanent residents of the prison town. Peter Wagner, Cincinnati OH July 18, 2003

by Peter Wagner,

July 28, 2003

In the words of U.S. Department of Agriculture demographer Calvin Beale: “A rural prison is a classic ‘export’ industry, providing a service for the outside community. Unlike some other rural services, such as recreation, the employment is year round.” Although rural counties contain only 20% of the national population, they have snapped up 60% of new prison construction. Like export processing zones in Third World countries, even the raw material is imported for final manufacture. In New York, for example, only 24% of prisoners are from upstate, but 91% of prisoners are incarcerated there.

The most troubling aspect of miscounting prisoners in this fashion is the potential to change the balance of political power between communities who stand on opposite ends of state crime control policy. Taking electoral clout from urban communities which are the most negatively affected by aggressive incarceration policy, and giving that clout to rural communities that benefit from prison jobs has the potential of launching a cycle of prison growth without a democratic restraint.

by Peter Wagner,

July 22, 2003

The State of Utah lost a potential 4th Congressional seat to North Carolina in 2000 after the Census Bureau counted overseas military in each state’s population, but refused to count over 14,000 Mormon missionaries as residents of Utah. The Census practice in regards to overseas military has been inconsistent, counting the military in 1970, 1990 and 2000 but not 1980. Other overseas populations are not counted.

The Salt Lake Tribune reported:

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled the on-again military count was not arbitrary, a decision [Jerrold] Jensen [public affairs chief for the Utah attorney general] views as favorable for Utah.

“The general rule is you don’t count U.S. citizens living aboard because they may never come back, but the Census Bureau created an exception for the military,” Jensen said. “If you can create one exception, you can create two.”

Or three. Almost all prisoners will complete their sentences and return to their home communities. Like missionaries, prisoners will most definitely come back.

Sources:

Ex-Utahn defends decision by bureau that cost state seat, by Elyse Hayes, Deseret News (Salt Lake City, Utah), January 10, 2001, p. A1

Leavitt may challenge Census count, may ask for Missionaries to be included in count, by Joe Baird, Salt Lake Tribune, January 6, 2001, p. A1

by Peter Wagner,

July 13, 2003

Sixty-five percent of New York State’s prisoners come from New York City. But even if the prisoner origins were not disproportionately concentrated in New York City, the geographic disparity would still be significant. One way of expressing the geographic disparity between the general New York State population and the prison population is with the idea of a population center.If everyone in New York State stood at their census address on a flat, weightless map of the state, the map would balance near Otisville in Sullivan County, just over the border from Orange. (See the red cross on the map).Ninety-two percent of New York State’s 71,466 prisoners are incarcerated in upstate prisons. The population center for the prisoners, on the other hand, is near Hamilton in Madison County over 100 miles to the north and west. (See the yellow cross on the map.)

Read more about prisoners and the census in New York

by Peter Wagner,

July 6, 2003

Update

It is ironic that Connecticut would value the distribution of federal aid in this way and then send residents out of the state. That issue aside, the Secretary of State’s valuation of federal aid that underlies this article appears to overstate the impact by blurring the distinction between federal aid per capita and federal spending per capita. Federal aid distributed to the states on a per-capita basis is more in the range of $1,000 a person. Still worth discussing, but smaller.

Readers should note that the $1,000 figure is not necessarily the figure to use when discussing the intra-state impact. The distribution within a state tends to match the state’s needs and politics more than the population into Census tracts. For example, the Census is a factor in determining how much federal highway funds a state gets. The state is likely to spend the money where road conditions, traffic and politics warrant.

Update: Apr 24, 2004

Although most state prisoners are housed within their state, a growing number of states are paying to incarcerate their prisoners in other states. (Federal prisoners may be incarcerated in any state, but the originating state has no control over where the sentenced prisoner is confined.) Most frequently, a state justifies housing prisoners out of state on the grounds that it costs less.

For example, Connecticut claims that incarcerating a prisoner costs $95 a day in Connecticut, and considerable savings can be realized by paying Virginia’s rate of $64 a day for each prisoner sent to that state. There are two typical arguments against out-of-state transfers.

First, increasing the distance between a prisoner and his or her family makes visits more difficult, increasing recidivism. Second, it’s better for a state’s economy to spend its money in the state. While $95 may be a greater expense than $64, at least the funds remain in the state.

The Connecticut Secretary of State estimates that the state receives $5,932 in various types of annual federal aid for each resident in the state. Per resident, that’s a loss of $16.25 a day, or 53% of the “savings” from sending prisoners to the “cheaper” Virginia prisons. Prisons are a profitable business in Virginia, first on a fee-for-service basis, and again from the Census’ practice of counting prisoners were they are incarcerated rather than where they are from.

Source: Shipping Prisoners Could Cut State’s Census Count, by Agnes Diggs, The Advocate (Stamford, CT) April 10, 2000.)