by Peter Wagner,

September 29, 2003

Mansfield, Ohio is a small city with 6 city council wards of approximately 8,600 residents each. The problem? Two large prisons (Mansfield Correctional Institution and Richland Correctional Institution) are both in the 5th Ward and their populations were counted as residents of the ward.

The City’s law director advocated for a redistricting plan that would at least split the prisons into two different districts, complaining that “Deanna [Torrence of the 5th Ward] is only representing 3,000 people (who actually can vote).” The City decided to keep the districts as-is.

The best solution for the city would have been to exclude the prisoners from the redistricting process as the majority of the prisoners are from outside Mansfield and its Ward 5. Only 1.26% of Ohio’s prisoners are from Richland County (564 prisoners), with a smaller portion being from Mansfield and an even smaller portion from Ward 5.

It makes no sense to use Census counts of state prisoners to divide up political power within the City of Mansfield. Of course, the best solution would be for the Census to count prisoners at home, not at temporary prisons.

Sources: Linda Martz, Taxpayers before wards, Mansfield News Journal (Mansfield, OH) November 26, 2002, p. 6A; U.S. Census, Ohio Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation.

by Peter Wagner,

September 22, 2003

Counting prisoners as residents of the prison town can skew the balance of political power within a rural community as well. As I wrote in Bogus data pumps up the rural population, the reported population of many rural counties with prisons can be significantly changed by as much as 5 or 10% as a result of counting mostly-urban prisoners at the prison. In counties with a legislative form of government, including the prisoners in the base population can significantly boost the weight of a vote in the prison town while diluting the weight of a vote in other portions of a county.

In Greene County NY, the county legislature proposed to include prisoners in the count. The two prisons in Coxsackie in the northeast corner of the county amounted to 6% of the county’s population. Of course, the prisoners can’t vote and few if any are from Greene County. Including the prisoners would have resulted in the town of Coxsackie getting 48% more representation in the local legislature than it was entitled to.

At the urging of residents elsewhere in the county, the Greene County legislature decided to change from previous practice and exclude the prisoners from the count. This was the correct thing to do. The change did not hurt the ability of the prisoners to get representation in local government (as they were not residents of Greene County in the first place), and it brought the principle of “one person one vote” to the local county legislature.

Unfortunately, this was not the practice everywhere in New York, and the diversity of approaches shows that contrary to assumption, counties are not obligated to slavishly use inappropriate Census data in their redistricting. According to a survey distributed by Saint Lawrence County, 14 counties included prisoners in their redistricting and 9 excluded them. (Ten of the prison counties did not respond.)

See also Exclude prisoners from local redistricting submitted to Daily Freeman, Greene County, New York, February 3, 2003.

by Peter Wagner,

September 15, 2003

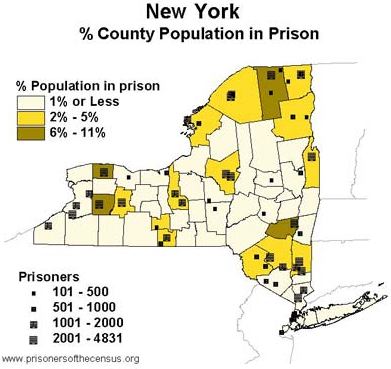

The presence of a prison in a rural area can have a huge impact on Census Bureau statistics about the town or county. In a number of counties in New York, prisons can make up more than 2% of the county’s population, and in the case of Franklin County, prisoners constitute almost 11% of the population reported to the Census.

by Peter Wagner,

September 8, 2003

In 1894, Michael Cady tried to register to vote using his address at the Tombs Jail in New York City. Jail inmates are allowed to vote, but he was convicted for illegal registration because the NY Constitution says that

“no person shall be deemed to have gained or lost a residence, by reason of his presence or absence … while confined in any public prison.”

The prosecution’s theory that that while Cady was allowed to vote, he could not vote in the prison district. Even through Cady was planning on staying at the Tombs forever, Cady must have — the prosecution argued — lived somewhere else before.

The highest court in New York agreed:

“The Tombs is not a place of residence. It is not constructed or maintained for that purpose. It is a place of confinement for all except the keeper and his family, and a person cannot under the guise of a commitment … go there as a prisoner, having a right to be there only as a prisoner, and gain a residence there.”

If calling your jail cell your residence gets you sent to prison, shouldn’t it be illegal for rural legislators to call prisoners their “constituents”?

Read more about Michael Cady in Importing Constituents: Prisoner and Political Clout in New York.

by Peter Wagner,

September 1, 2003

“On April Fool’s Day this year state prison wardens gave more than 5,600 inmates time off from their hourly-wage jobs to fill out their census forms. The wardens know how many inmates they have, of course, but only the prisoners know the answers to the more detailed questions posed in the national headcount. So each inmate who cooperated was paid $1…

“A dollar may not sound like much of an incentive, but prison wages are often less than 75 cents an hour….

“The census, as Minnesotans were repeatedly reminded last spring, means money for basic services. The detailed demographic information people offer up on their census forms every ten years translates into federal dollars to help their communities pay for everything from affordable housing to road repair. Prisoners, however, don’t get counted as residents of their former neighborhoods. Instead, the census adds them to the populations of the communities where they are serving time.

See: Prison Math by Meleah Maynard in City Pages, October 25, 2000.